Concepts:

- aesthetics

- aesthetics (and poetics) of conformity

- aesthetics (and poetics) of opposition

- poetics

- samizdat

- tamizdat

- dogmatic aesthetics

- propaganda

- socialist realism

- surrealism

- formalism

- postmodern, postmodernism

Competencies:

Through the content and activities of the course, students will

(Knowledge)

- get to know the main spaces of literary life in the socialist era;

- have an overview of the context of literary life especially in their own country during this period;

- understand mechanisms of control and censorship on literature in the regime;

- understand variegated strategies in different contexts and times adopted by the writers and stakeholders in literature;

- understand the complex interplay between conformity and resistance in literature;

- get to know literary forms of propaganda and their mechanisms;

- understand the principles of socialist realism and some other concurrent tendencies in aesthetics;

- understand the dialectical connection between texts and context,

- reflect on the history of reception of the texts;

(Attitudes)

- be open to a complex analysis of opposition and conformity in literature during the socialist era;

- be open to an aesthetic approach to literature and texts;

- be open to the plurality of aesthetics;

- assume a non-judgmental attitude while approaching texts with reflections on someone’s own values;

- esteem the autonomy of art (literature) from political restrictions;

- esteem examples of different forms of resistance in literature against the restrictions of the regime;

- be open to the interpretation of texts during this historical period also as a tool for understanding better our own beliefs, context and attitudes;

(Skills)

- be able to find information on literature and literary life in their own country and local context;

- be able to interpret literary texts by using poetic categories relevant in the studied period;

- be able to identify and use the characteristics of propaganda literature;

- be able to consider the context of the texts and their reception in their interpretation;

- be able to identify characteristics of socialist realism in literary texts (especially in poems).

by György Mészáros

Introduction

In the era of state socialism, art (artistic expression, activities and forums) was important both for the transmission of the regime’s ideology and for cultural resistance against it. In other lessons, you can also see how different artistic activities and artefacts served as tools of control or as opportunities for opposition (artistic events, products, circles, samizdat, subcultural expressions, etc.).

Literature is also part of this story. Literary works in a wide sense (poems, novels, dramas but also lyrics of songs), forums and communities of authors, events, etc. were important texts and “spaces” in the regime. In these texts and “spaces”, propaganda, official ideology, official aesthetics (principles of beauty) and poetics (theories of literary forms) were expressed and met the ideology, aesthetics and poetics of opposition.

If we study the literature of an era, we might understand its history better. However, the main aim of this lesson is not to deepen historical understanding of socialist regimes, but to understand how this inter-twinning of control, ideological influence and opposition and resistance worked in literature of the era understood in aesthetic terms (especially looking at texts which of course were surrounded by events, forums, communities…). So, this lesson is a literature lesson with historical dimensions, and not a history lesson with examples from the literature. It would be impossible to outline the so variegated scenes and texts of literature in the respective countries. So, the lesson can only offer some illustrations and examples of these complex tendencies. Although literature consists in very different genres, but in this lesson, we will focus on poems in terms of texts, because they are the most accessible sources for a direct interpretation.

Four texts and their interpretation

Please read the excerpts in the Appendix from the poems Verses in Remembrance of the Revolution; Axman; Engagement and If I was a rose (in the Appendix) possibly without checking anything about their context and authors, and try to answer these questions before you go on with the text of the lesson:

- what kind of feelings you have reading each of the verses?

- what do they mean to you personally?

- please try to identify the symbols in the excerpts:

- volcano, miracle, mirage; blowing down the capital, ax; employment; flag, winds

- if you do not understand the meaning of these symbols try to search for them or ask help from your teacher

- in relation to state socialism what kind of messages do these verses have?

- which are the texts that conform to and the ones that oppose the official ideology? how? how much explicit is the message in the texts?

- what do you think: what is the chronological order of the texts, and when were they produced? (try to guess at least the decade or the period: which part of the 20th century? no problem if you don’t know the exact answer, this is not for checking your historical knowledge, but only your impressions about texts and periods)

Actually, it is interesting to see the context of the three poems. They are in a chronological order. Of course, these are just excerpts, so it is not possible to outline a full and proper interpretation of the poems, but the given verses are sufficient to understand some elements of interpretation in the context of state socialism.

The forth one (If I was a rose) is János Bródy’s lyrics based on the melody of a Hungarian folk song. It was published in 1973 on the disc of Zsuzsa Koncz (Sign language), but after two weeks, it was confiscated and banned. The meaning of the verses ia figurative. It embodies the typical tendency of the cultural opposition in the 1970s, which tried to express its criticism toward the political regime in an implicit way using ambiguous terms. However, the metaphor this song used was “too evident” for the authorities of the socialist propaganda. The verse about the street was not simply interpreted as a text against war, but it was also considered an allusion to the defeated revolution in 1956 in Hungary (the tanks are the Soviet tanks on the streets of Budapest). The flag and its tightness were seen as symbols of resistance against ideological and political influences from abroad (mainly from the Soviet Union: that is why the song was sang with the “Eastern winds” version by the audience during some concerts later on, although the original text had “all the winds”).

The third one (Engagement) is in the Registry. The poem was the collective work of and entire group. They tried to publish it in Romania in 1974, but the censorship prevented it. “It was first published two years later in a changed form in the West German cultural magazine Akzente. Zeitschrift für Literatur (No. 6/1976; Totok 2001, 22–23). The poem uses wordplays to suggest the omnipresence of coercion in the society they lived in and it represent a subtle critique of the state–citizens relation in Ceaușescu’s Romania. The authors played with the meanings of the German word Engagement which in the poem could be understood both as employment and (ideological) commitment. In the second part of the poem, the authors suggest overtly and ironically the coercive character of the state–citizen relation in the society they lived in and the impossibility of the latter modifying this relation either in ideological or in practical terms.” The poem shows how oppression influences everyday life, people’s behavior, and how it deeply permeates the society, private life and even people’s personality. This is similar of what Orwell represents in his famous novel: 1984.

From today’s perspective, the first two might seem propaganda literature of socialism, however originally, they were not. The second one (Axman) is Attila József’s poem became victim of the censorship in the interwar Hungary: it was confiscated by the right-wing conservative cultural politics in 1931. It conveys explicit opposition, but in an earlier historical period, when communist thoughts were persecuted and communists were criminalised. Attila József was member of the Communist Party for a certain time, and wrote some poems with anti-capitalist, anti-establishment sentiments, however, he died in 1937 — much before communism became the state ideology in Hungary. He is one of the most acknowledge poets in Hungary. Similarly, the first poem (Verses in Remembrance of the Revolution) was written by famous, Nobel Prize-winning Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert in 1923 for the fifth anniversary of the Soviet Revolution, so not during the period of state socialism. Seifert was also a member of the Communist Party, but later he distanced himself from the official Party lines. This poem was born in his early period when he had an idealistic view of communism and the Soviet Union that would bring a new era of happiness for working class and oppressed people whom advocacy was a persistent topic in his literature all over his life.

Both poems were originally poems of political resistance. However, for instance the Axman was used in communist festivities, was taught in school as important poem, thus, it became part of a certain propaganda literature. These examples show, how literary texts can be used for different political purposes, and we can also see that the meaning of a text depends on its impact, reception and contexts.

Context: the world of literature during state socialism

Before looking at more examples of the aesthetics of the socialist era, it is useful to take a look at the variegated forms of the world of literature in this period without entering deeply into this topic. The main elements of the context of literary production consisted of publishing houses, journals, writers’ unions, events and controlling institutions of the state or the party.

Publishing houses had an important role because they published international works, new talented writers and old ones, so they actually influenced what could be read by the people, and they were under ideological control, of course. Beside the official publishing houses, they were underground ones like the Polish NOWA.

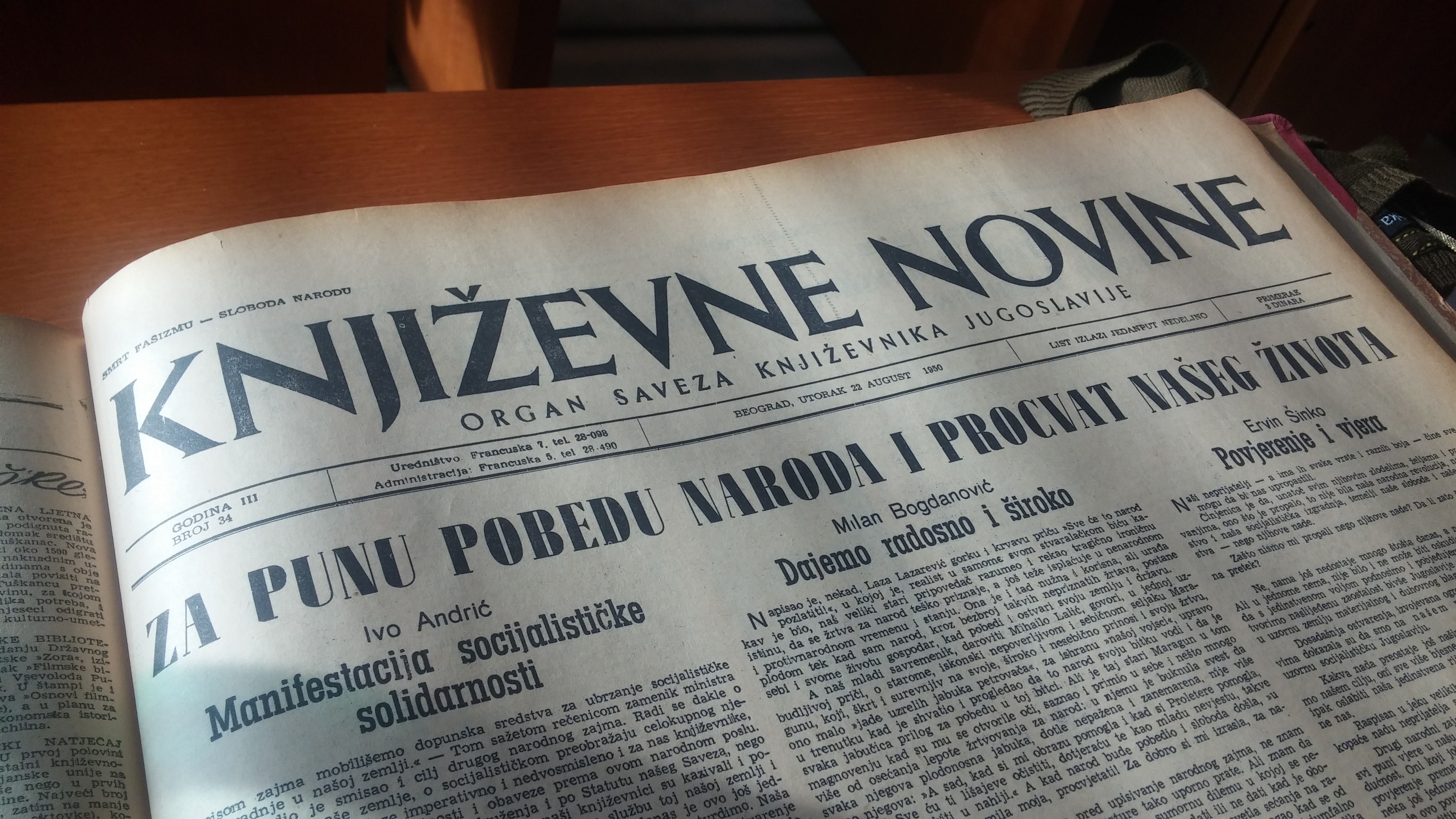

Journals were important spaces were short novels, poems, essays could be published as well as discussions and debates could be held. These periodicals gave platform to different kinds of literary works and critics. Some of them often pushed the boundaries of the ideological control, and they were banned for certain periods, e.g. Književne novine in Yugoslavia, Mozgó Világ and Tiszatáj in Hungary.

Književne novine (Literary News) Credits: Sanja Radovic

Writers’ unions represented important organizations where tendencies of both conformity to the official lines and opposition or critical views were represented. Sometimes, even after active participation in the Sovietization of literature, they could construct a certain internal autonomy and even resist to the imposed tendencies in the post-Stalinist period (e.g. the Moldavian Writers’ Union or the Lithuanian Union of Writers. In the 1980s, some of the unions were important sights for the growing critique and opposition against the regime (e.g. the Hungarian Writers’ Union with its annual writers’ camp in Tokaj).

Events like book launches, meetings of artists and congress of writers were another platform were one can grasp the debates, scenes, trends of literary production in a country. For example, in the lesson about Religious opposition, the Polish Artistic Week was already mentioned as an event of dissent and opposition. Congresses of Writers Union were events of debate, confrontation or cultural opposition. During the 5th Congress of the Lithuanian Writers Union in 1970 the older generation of writers criticized their younger colleagues because of their “modernist” style did not focus on the content as it was expected in socialist realism (see below), and they called their position as “formalism”. While, five years earlier, in 1965, during the Congress of the Moldavian Union of Writers, the different generations forged an alliance and criticized the Russification of Moldavian culture.

In every country, there were institutions controlling literary production. For example, the Ideological Commission of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia, the Latvian Communist Party Central Committee or in Hungary, a prominent politician of cultural affairs György Aczél (member of the Central Committee of the Party) whose decision formed the cultural-artistic life during the Kádár-era (here is an event about the “Aczél Era”.)

It is important to note that several “national” publishing houses were also found in Western countries. They published those works, which were (or would have been) prohibited in the respective country (tamizdat), and there were several writers who emigrated and produced literature in exile (e.g. Milan Kundera, Ivan Blatny or Danilo Kis). Some of these authors were (re)discovered after the fall of the regime.

Conformity

It is not always easy to define what conformity to the ideological lines means in literary terms. On the one hand, explicit critiques against the regime and its ideology were certainly not allowed, thus, critical literary works remained unpublished (e.g. Knuts Skujenieks poems written during his detention) or banned (e.g., the case of Tiszatáj) and/or distributed in samizdat (e.g., Petko Ogoyski’s poems). On the other hand, there were some expectations towards the content and aesthetics, from the party and the official “architects” of cultural life, but these expectations were not always imposed, so literature as art and the artistic production could have reached a certain autonomy and freedom especially after the Stalinist period. And, as we will see in the sections about socialist realism and opposition, the boundaries of conformity and opposition were not always clear.

It is also important to note, that in the different periods of state socialism, the control measures were also different, and the more direct propaganda literature, that represents absolute and evident conformity and submission to the regime, were strongly present only in the harshest period of oppression.

Propaganda literature

The term propaganda is usually used in a negative sense. It means a mode of communication that wants to influence society and transmit certain messages or ideas, often in a manipulative way. Propaganda literature are poems, dramas, novels and other literary works, etc. that have this ideological and manipulative character. This kind of literature was particularly present in the first (Stalinist) period of the regime, but where personal cult was strong (like in Ceausescu’s Romania), it remained important even later on. The most extreme forms of propaganda literature often had celebratory nature. They were celebrating the successes of the Party, the Soviet Union or the greatness of the Leader. In the 1950s, authors might have been or have felt forced to write propaganda works. For example, the Hungarian Gyula Illyés who secretly wrote a powerful resistant poetry about tyranny in 1950, contributed to a volume that hailed the Hungarian authoritarian leader for his 60th birthday in 1952. Union of Writers contributed a lot in the promotion of propaganda literature in the Stalinist period (see above).

Propaganda literature often delivers a simple, easily understandable message. It is dogmatic frequently following predetermined schemes. These works are very much connected to that period when they were written and published, and they become forgotten soon. The cultural memory and the canon in Eastern Europe have cast up propaganda literature and it is now difficult to find examples on the Internet (especially in English translation). However, it is interesting to read some pieces of this literature to grasp the special characteristics of its aesthetics.

Songs from the communist era with their lyrics might be considered part of this propaganda literature. The message of the lyrics was underlined by the force of the music. Some pieces are accessible on the Internet, and in some countries, they have a sort of popularity, they seem to be funny, and younger generations sing them with some irony, or some members of the older generation remember them with a certain nostalgia. Their reception is totally different now than in the socialist era.

Socialist realism

Socialist realism was the imposed aesthetics by the regimes. Opposing it in samizdat or tamizdat publication meant opposition against the authoritarian system (like the tamizdat publication What is socialist realism? that questions its fundamental assumptions). However, socialist realism was not a simple ideological and dogmatic aesthetics, it also had very different forms, and it cannot be described with one set of criteria that can be imposed. Socialist realism also reached beyond the borders of socialist countries, and were adopted by Western writers (like Luis Aragon or to a certain extent Pablo Neruda), too. In the previous sections, you could have already understood some of the dimensions of this approach to art (and literature). Maxim Gorky, the Russian writer, and one of the most prominent representatives of Soviet socialist realists, during the Congress of the Union of Writers in 1934, gave a speech about the role of literature in socialism. Some sentences of this speech show that behind this aesthetic one can find a clear project of emancipation and social change in relation to the working class:

” The culture of capitalism is nothing but a system of methods aimed at the physical and moral expansion and consolidation of the power of the bourgeoisie over the world, over men, over the treasures of the earth and the powers of nature. The meaning of the process of cultural development was never understood by the bourgeoisie as the need for the development of the whole mass of humanity. (…) The peasants and the workers were deprived of the right to education – the right to develop the mind and will towards comprehension of life, towards altering the conditions of life, towards rendering their working surroundings more tolerable. The schools trained and are still training no one but obedient servants of capitalism, who believe in its inviolability and legitimacy.”[1]

In order to fulfil this aim, art and literature should follow certain guidelines according to this Congress, and these principles were the foundation of socialist realism.

According to these guidelines, socialist literature should be

- realistic: representing the reality of capitalism and the working class, especially typical figures and scenes of everyday life;

- proletarian: relevant for the workers, connected to their lives;

- ideologically committed: serving the ideology that can debunk capitalist (false) ideological constructions;

- socially active/revolutionary: having the purpose to enhance social change;

- politically committed: supporting the Party in its endeavor to defeat capitalism.

These are, of course, just some general lines, that were applied in different ways according to the different socio-political situations. As we have already seen, during the Stalinist period the control was harder and direct propaganda was important, while even in those times, different works were published, not totally conforming to these aesthetic principles.

Other factors influenced the expectations in various countries and times. Like in some Soviet States, Sovietization also meant Russification. There were different attitudes of the regime towards national tendencies in different contexts, indeed. Sometimes, internationalism was pushed, in other contexts national literature was acknowledged and supported.

Some of the authors who were supported or tolerated by the regime didn’t follow the socialist realist guidelines, or others who followed, but were critical with the regime might not be supported.

E.g., in Yugoslavia, where the ideological constraints toward literature were less strong already from 1949 (because Tito’s split from Stalin), Ivo Andrić enjoyed and acknowledged a privileged position in literary life, at the same time, he was respected internationally, as well (he won the Nobel-prize in 1969). His prose was realist, but was not a typical example of socialist realism. He was blamed of being opportunistic by some people.

Another important figure of that period was the Croatian Ivan Aralica who despite being a party member and political figure for some years always remained critical toward the regime presenting how it created dogmatic consciousness in marginal people, and this domination eradicated old moral codes without substituting them with new ones. Later, constrained to leave his official posts, he was interested in the relationship of the authorities and the individual.

In Hungary, Gyula Illyés was one of the most acknowledged authors as he had left-wing views and was part of the writers “from the people”. Another Hungarian poet: Ferenc Juhász had also similar realist and folklorist roots, and became a prominent figure of Hungarian literature. He was sometimes supported and acknowledged, but sometimes attacked during the socialist decades. Attacks were due especially to the fact that his style radically changed in the 1950s and he introduced a new mythic style in Hungarian literature.

One of the most interesting examples in which the boundaries of opposition and conformity remained opaque, is Adam Ważyk’s A Poem for Adults published in 1965 in the official journal of the Association of Polish Writers. It is a socialist realist poem, but it criticized the Stalinist regime, and especially in its reception (its denouncement by the party and its wide distribution), it turned into a clear dissident poem.

Please read the text and try to answer the following questions:

- What are the socialist realist characteristics of the poem? Try to compare the above mentioned criteria and the text.

- How criticism is expressed and reinforced by the text?

Poetics of resistance and opposition

In the above-mentioned poem of Adam Ważyk, one can see an example for the poetics of opposition. It uses the official socialist realist genre and its content is also in consonance with Marxist ideology, but it criticizes the given political system. It is an example of literary opposition that remains in the framework of Marxist tradition. Nevertheless, poetics of resistance were not uniform either. In this section, we will see some examples of this. Before that, it is also worth mentioning that literary resistance was not only a matter of poetics. It influenced people’s everyday life, career, health and in some extreme cases it costed the life of some authors. (Like the case of Grzegorz Przemyk who was murdered in 1983 by the Polish police). But the goal of this lesson is to interpret texts in the light and context of historical happenings, and not of historical happenings in the light of the texts. Therefore, in the last section of this lesson, we will see some forms of aesthetics of opposition and offer two concrete texts for interpretation.

Some texts present concrete critiques toward the system, or celebrate or commemorate dissident heroes (e.g., Hungarian prime minister Imre Nagy during the 1956 revolution, who was sentenced to death in 1958). Hungarian poet Gáspár Nagy (an important figure of the opposition in literature), published a poem against the restriction of the liberty of press, and another one that was a clear call for the reburial of Imre Nagy. Both poem was censored.

Some texts denounce the deeds of harsh oppression of the regime like the Romanian Paul Goma’s book: Gherla about his imprisonment , or Virgil Ierunca’s book: Pitești presenting the “re-education” through torture using the narratives of former prisoners. These works were published in non-socialist countries.

Other texts tested the limits of censorship. For instance Ana Bladiana’s poem for children that presents her own tomcat: Arpagic. He is described “as a superstar who is acclaimed by everyone, greeted with the traditional bread and salt and with grand pomp wherever he goes, while all those around him obey his orders.” These scenes reminded everyone to Ceauşescu’s (the Romanian dictator) working visits all over the country.

Ana Bladiana, Credits: http://www.bloodaxebooks.com/ecs/category/ana-blandiana

Some poems could slip through censorship and were published because the censors did not understand the clear oppositional message of the text. This is the case of Gerhard Ortinau’s poem written in German: The street ballad of the ten parts of speech of the traditional grammar. Its publication was also due to a certain liberalisation and relative autonomy of cultural institutions in Romania during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The poem represents the dictatorship with metaphors and puns, with absurd statements such as “a pronoun was arrested”, and expresses non-conformity with its spelling, too, avoiding the usual capital letter for nouns in German.

Other texts also were not so directly critical toward the political regime. They used more subtle allegories, metaphors, figurative expressions that contains dissident messages: e.g., the texts offered at the end of this section, or Petko Ogayski’s samizdat work in which critique is hidden in the form of allegorical folk tales, jokes, poems and aphorisms. In other cases of indirect resistance, the chosen and represented content is different from the one expected by Party guidelines (national values and dimensions against internationalization; personal and individual freedom highlighted, etc.)

One of Ogoyski’s Samizdat Publications: Ogoyski, Petko (1981). Tritsvetie. Trohi ot hlyab. stihove i aforizmi [“Tricolour. Bread Crumbs. Poems and Aphorisms”] Sofia. Credits: Anelia Kassabova

Manuscripts of poems written by Knuts Skujenieks in detention, from which collection of poems “Seed in Snow” was composed. Credits: National Library of Latvia

Another way of literary resistance was translating foreign literature that represented different aesthetics and brought new contents to the local literary world, often not in line with the official politics of culture. An interesting example of this is the former State President Árpád Göncz’ who, beside other dissident activities, translated a lot of authors, among others: Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

Finally, a clearly aesthetic opposition was also present during state socialism. It meant criticizing socialist realism and outlining another kind of aesthetics, or simply following other poetics as an author. As for the critique of socialist realism, we have already mentioned Andrei Siniavskii‘s article that repudiated the idea that literature should participate in social activism and want to define and transform reality. Another way of similar opposition is represented in the Manifesto of Socialist Surrealism that maintains the element of change and social transformation of socialist aesthetics, but links them to the irrational, joyful spontaneity. A third approach was followed by the underground periodical ‘brulion’ that contested both the socialist regime and the dissident subculture embracing postmodernism (characterized by questioning the humanism of modernity with fragmentation, textual games, refusal of evident meanings, paradox, unreliable narrators, authorial self-reference).

brulion: literary and cultural periodical. From the Polish Underground Publications Collection at Polish Library POSK in London.

There were a lot of authors who strongly opposed the official aesthetics with their work. Among others, it is worth mentioning Péter Eszterházy‘s postmodern, textually fragmented novels, or György Petri‘s subversive, self-reflexive and “anti-aesthetic” style (he was also an important and iconic figure of the opposition and samizdat literature in the 1970s and 1980s in Hungary), or the performances of the “mad poet” Jiří Fiala whose independent lifestyle itself was a protest.

Please read these three following poems in the Appendix:

Vizma Belševica: The Notations of Henricus de Lettis in the Margins of the Livonian Chronicle

Edvard Kocbek: Microphone in the Wall

Knuts Skujenieks: To a Dandelion Blooming in November

They have certain oppositional dimensions in quite different ways. Try to identify and interpret them.

Some information and questions for the interpretation:

Vizma Belševica: The Notations of Henricus de Lettis in the Margins of the Livonian Chronicle

Rolf Ekmanis writes about Belševica’s poem: “[The poem] juxtaposes intense, accusatory poetic comment with the pious thirteenth-century chronicle and tells the story of pillaging, burning, rape, and murder inflicted on a small nation by a large and powerful one in the name of an ideology – here, Christianity. (…) The Livonian Chronicle, known in the original Latin as Heinrici Chronicon Livoniae, is judged to have been written between 1225 and 1227 and describes mainly the progress of the German conquest of Livonia between 1180 and 1227. Although the events occur some eight hundred years ago, Belševica’s poeticized “notations” are conspicuously timely. To quote the Latvian poet and critic Gunars Saliņš, among the elements that lend Belševica’s story its remarkable contemporaneousness is <<the conspirational urgency with which her Henricus engages the reader. In this, Belševica’s conception differs strikingly from the ways in which similar historical material has been treated by most other Latvian poets. Whereas the traditional heroic epic ballade, no matter how splendidly written, tends to present the past as something memorable and yet remote and unredeemable, Belševica’s poem renders history with the immediacy of a news broadcast on a current political-and personal—crisis>>”

What does ‘writing notes on the margins’ recall for you? Have you ever done it, especially to write a different interpretation of the original text? Would you do it? With which or what kind of text? How much would it be different from the original? How these notations in the poem was different from the “original”, and what does this difference express about the regime? How can literature offer possibility to write, express opinion against the official interpretations? What are the limits of this expression?

Edvard Kocbek: Microphone in the Wall

Edvard Kocbek: was Christian socialist, who joined Tito’s partisan resistance movement. He fell from political grace in 1952 because of his collection Fear and Courage, which were stories about moral dilemmas of the partisan movement (something that was not to be questioned in the Tito era). In the next decades he suffered from censorship and surveillance. His situation is graphically exposed in the poem: “Microphone in the Wall”.

Pay attention particularly to the images of silence and (loud) voice in the poem. Have you ever had any similar experience (or heard of any similar experiences from others) when you (or they) were constrained to be silent or you (they) remained silent as a form of resistance, but you (they) wanted to say: “…my time has arrived,/ and I insult you, curse you,/you impostor, poisoner…” and „I am who I am”… How is that experience different from the one depicted in this poem? Consider also the historical circumstances of the poem. What is the revenge in the poem? In which sense can a poem be a revange (think about the long term nature and re-interpretations of poetic texts, too)?

Knuts Skujenieks:To a Dandelion Blooming in November

As it was mention above, Knuts Skujenieks wrote poems in the Gulag during his detention between 1963–1969. This is a very different kind of oppositional literature. This poem is not a direct protest like the previous two. As the poet wrote (cited by the Registry): “The initial shock and protest gradually changed into a fight into prison within myself”.

How the metaphor of the blooming dandelion expresses this internal fight? What does the home mean in this situation of prison? What kind of personal resistance and opposition is depicted with this image? Can you relate it to any of your experiences of resistance? How this poem could have been oppositional if it had been published during the ‘70s in Lithuania? How would it (the published text) be different from the resistance expressed in the poem by the poet?

Tasks:

- If you studied Orwell’s 1984, try to analyse how the mechanisms of propaganda that is described in it, could be applied to the texts of propaganda that you have found.

- Write (individually or in group) a parody of propaganda poems

- Search writers in the Registry, who were part of your literature studies (in your country), and see in which context they are mentioned, what was their relation to the regime? Prepare a written or oral summery.

- Group project: search periodicals, unions, organizations both in the registry and in your local context (from the given period). Collect texts from these platforms, and prepare a small performance that somehow resonates with the atmosphere of the period and context of the texts.

- Create oppositional poems or short novels (individually or together): choose a topic (it might be something actual) that you would like to criticize, and creat something that express resistance or opposition. After you read it, discuss it with the others how it might be different from the oppositional literature that you studied. Try to find actual examples of “oppositional literature”, and do the same. Try to identify some specificity of the oppositional literature of the socialist era.

Appendix: texts

Verses in Remembrance of the Revolution

(excerpt)

The autumnal mist in the walls of the street

was swiftly broken by metal files of automobiles,

and red banners, of which there were thousands,

above the heads of the crowd fused into a blazing fire,

and those were not long telescopes on the lookout tower,

nor was there hardly a bearded astronomer,

those were gun carriages of cannons, as Red Guardists sought

to tear down to its foundations the old order,

and on the horizon, on street pavement, and in poor soil,

as well as in the human palm,

they discovered the five-pointed star, which will shine

like the morning star from afar,

it was no dormant volcano that erupted and yet Europe

trembled,

and rattle did the windows of governments and departments,

it was no lava, which was flowing tepid all about in streams,

it was blood, blood, blood of humans,

to that polyphonic melody we listened with piety,

and fools in those days we did not believe,

thinking that all this was not at all possible,

that it was not force, but that it was a miracle,

and when overnight within reach

a new land suddenly emerged,

we thought it was a mirage.

(…)

[Source: Seifert, J. (1999). Early Poetry of Jaroslav Seifert. Northwestern University Press]

Axman

(excerpt)

– Come on, blow down the capital, do not wail,

do not cry for any small shards!

If you hit around the fate,

the genteel peasantry screams –

the wide ax smiles.

[my own literal translation]

Engagement

(excerpt)

I’ve been employed for too long

I don’t want to be employed anymore

I have also been employed too long

yes

with you

also with you

I am no longer employed

I am not employed either

yes yes, me neither

in vain, who was once employed

remains employed forever

[Source: http://cultural-opposition.eu/courage/individual/n25267]

If I was a rose…

(excerpt)

If I was a street, dear, I’d be always pristine.

Every blessed night, in the light I would bathe.

And if one day tanks stomped their tracks upon me.

With a cry, the earth would collapse underneath me.

If I was a flag, dear, you’d never see me waving.

I’d be wrathful with all the wind around me.

I’d only be happy if they stretched me tightly.

So, I wouldn’t be the play-thing of all the winds (another version: the Eastern winds) around me.

[Source: https://lyricstranslate.com/en/ha-en-rozsa-volnek-if-i-was-rose.html#ixzz5ImLJpbKZ]

Adam Ważyk: A Poem for Adults

14.

They shouted at the ritualists,

they instructed,

enlightened, and

shamed the ritualists.

They sought the aid of literature,

that five-year-old youngster,

which should be educated

and which should educate.

Is a ritualist an enemy?

A ritualist is not an enemy,

a ritualist must be instructed,

he must be enlightened,

he must be shamed,

he must be convinced.

We must educate.

They have changed people into preachers.

I have heard a wise lecture:

“Without properly distributed economic incentives,

we’ll not make technical progress.”

These are the words of a Marxist.

This is the knowledge of real laws,

the end of utopia.

There will be no novels about ritualists,

but there will be novels about the troubles of inventors,

about anxieties which move all of us.

This is my naked poem

before it matures

into troubles, colors, and odors of the earth.

15.

There are people tired of work,

there are people from Nowa Huta

who have never been in a theater,

there are Polish apples unobtainable by Polish children,

there are children scorned by criminal doctors,

there are boys forced to lie,

there are girls forced to lie,

there are old wives thrown out of homes by their husbands,

there are exhausted people, suffering from angina pectoris,

there are people who are blackened and spat at,

there are people who are robbed in the streets

by thugs for whom legal definitions are sought,

there are people waiting for papers,

there are people waiting for justice,

there are people who have been waiting for a long time.

On this earth we appeal on behalf of people

who are exhausted from work,

we appeal for locks that fit the door,

for rooms with windows,

for walls which do not rot,

for contempt for papers,

for a holy human time,

for a safe home,

for a simple distinction between words and deeds.

We appeal for this on the earth,

for which we did not gamble with dice,

for which a million people died in battles,

we appeal for bright truth and the corn of freedom,

for a flaming reason,

for a flaming reason,

we appeal daily,

we appeal through our Party.

[Source: http://konicki.com/blog2/2009/06/04/june-4-a-poem-for-adults-by-adam-wazyk/]

Vizma Belševica:

The Notations of Henricus de Lettis in the Margins of the Livonian Chronicle

| IT WAS THE YEAR 1212 OF THE LORD’S INCARNA- TION AND THE BISHOP’S 14th YEAR FOR THIS WITH THE PILGRIMS REJOICED THE WHOLE LIVONIAN CONGRE- GATION * |

Long since, the water in truth’s wells is bitter, Mixed with lies, it does not quench the thirst. Fruit plucked unripened from the tree of knowledge Has stripped the teeth. The mouth will go on hurting.Full brims the cup of disillusion and be- lated doubt.Rome like a jealous wife demands That love be sworn to her in public At every step… With spying eyes she reads Between my lines, that she owns not This heart, once so naive and yielding. The translator falls mute. And thoughtful grows the jester. And in dreams Courish boats sail down to Riga.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I know — they won’t arrive. And, if they do, In vain the blood. A scream above the walls. And in a grave of fire we shall go silent. And the clenched jaws will bitter ashen dustBecome. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Still the boats sail and sail. And women sing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * |

| AND THE BISHOP SENT OUT TO ALL THE LATGALIAN AND LIVONIAN CASTLES AND TO ALL THE LANDS WHICH BORDER ON THE RIVERS DAUGAVA AND GAUJA AND GATHERED A LARGE AND MIGHTY FORCE * |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Our rivers turn arid. Our menfolk are craven. Blush for shame, our little sons, Your fathers blush no more. Our blood gushes out, Eyes feed the ravens. Foreign standards fathers bear, Serve in foreign legions. Calm the birch’s whiteness, Quick the axe’s stroke. Only — arm raised overhead — Foreigners, attend! Easily the tree is felled. Not the roots extracted. Our enmity is trickling water. And your might — a rock. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I want to burn. Give me the funeral pyre! Long was my life. But my life’s waking — short. The highest of my father’s sacraments —To climb toward heaven on a towering flame And scream out the injustice by which my nation With fiery iron was beset and slaughtered. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Is it injustice? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * |

| BUT ALSO THE LIVONIANS AND LATGALIANS BEING MORE RUTHLESS THAN OTHER NATIONS LIKE THE SERVANT OF THE GOSPELS NOT ENDOWED WITH MERCY ON THEIR FELLOWMEN SLAUGHT- ERED COUNTLESS PEOPLE KILLING ALSO SOME WOMEN AND CHILDREN AND DID NOT WISH TO SPARE ANYONE ON THE PLAIN AND IN THE VILLAGES * |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . O, traitorous nation, is it worthwhile To live for you, lay down my life for you? O, cur-like nation! In place of bread Your master dips in blood a roadside pebble. Gulp then your blood! And the stone gulp with it! And wag your tail! You have earned it well. O, servile nation! In sweet joy you tremble Because the master whips your brothers Instead of you. Waiting, bare your teeth To fall upon a brother’s bloodied nape, For in the master’s hand a medal glitters To be bestowed on you, when flesh with iron scourged Stops twitching. And once again a green branch Will be severed from the verdure of your vital force O swordsman’s jubilation! He can With your assistance forge the axe for you. When your obliging face grows too re- volting, Where is that Judas tree in which to hang myself, Your, slavish nation, most abject slave, Owned by the crusaders with sword and verse. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * |

| …AND TO THE BISHOP AKO’S HEAD AS A TOKEN PRESENTED OF VICTORY AND FULL OF JOY HE PRAISED GOD * |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Feet in heavy honey steeping goes my master’s horse. Yet this night in honey scarlet father’s head will soak. In my master’s sword the silver glitters and the gold, Brightly, brightly will it flash above my mother’s breast And my master’s riding cloak — pure and silken snow. How down in the darkening orchard shall my sister scream… Goading steed, into the smooth flanks now the sharp spur dieings. Acrid in my master’s footsteps charing coals will linger. In a parchment roll remain will the servant’s writing, That the Lord of Sabaoth was in His mercy by us, And Our Lady Mary also — flower of innocence. Oh how in the darkened orchard now my sister screams! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * |

| AND AFTER THIS FASHION THE INTRACT- ABLE AND TO PAGAN MATTERS MUCH DEVOTED NATION WAS LED BY THE VOICE OF CHRIST STEP UPON STEP UNTO THE YOKE OF THE LORD AND ABANDON- ING THEIR DARKNESS THEY GAZED FAITH- FULLY UPON THE TRUE LIGHT WHICH IS CHRIST * BY MY BEST KNOWLEDGE AND CON- SCIENCE I HAVE SAID NAUGHT BUT THE TRUTH TO ANYONE’S CREDIT TO ANYONE’S CENSURE |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I write, and from the words blood does not drip, And the barbed bitterness of letters does not gash the page. You, Jesus Christ, over my shoulder read How Godfearingly for your fame I lie. O Christ, your kingdom shall come over us, One god and tongue. And nation also one. I see the Latvian land with crossnails hammered To the surface of your holy meekness. Now what, you gentle one, our mourn- ful songs, What harm do midsummer’s wild blos- soms do you? But not of flowers — of thorns the bloody crown About the head should be… With pike- points must be ploughed The wineyard of the Lord across our bones And brains. Not a trace left, or thought. And our destruction — one more sunset That in unerring concept Rome may dawn Over the earth… . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Oh, let your faithful servant Still endure it. I greatly fear That I shall rise against you, Christ. From the dissembling cross ripped, naked, Beneath your slave’s feet into dust you’ll crumble. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .From dwellings blasted by the ashen winds They’ll come one day and ask me: why At heaven and your nation do you rage? Do we lack desolation, that our shame Should still be sown abroad? Are we not mocked Enough without you? And I will answer. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Scream, my nation! Writhe! Into your wounds I will pour salt, that you may forget Nothing. Grow in that painful hatred which is holier Than tenderest forgiving. I die With you, that you may be reborn. You shall Hoard death, calamity, disgrace and shame! And weep! Your tears will turn to steel When the time comes. And evil will be visited By iron rain. My hand is feeble And cannot exact for injuries. But words — they are a sword held double-edged Above their castles and above your homes. |

| 1968 | Translated from the Latvian by Baiba Kaugara |

[Source: http://www.lituanus.org/1970/70_1_03.htm ]

Edvard Kocbek:

Microphone in the Wall

We are finally alone

you and I,

but (don’t even think

of taking it easy or resting

for your work is just now starting.

You will listen to my silence

which is loquacious

and draws you to the depth of truth.

Listen carefully now,

you beast with no eyes or tongue,

monster with ears only.

My spirit talks without voice,

shouts and screams inaudibly

with joy to have you here,

you Great Suspicion,

hungering for me to reveal myself,

My silence is opening books

and dangerous manuscripts,

lexicons and prophets,

ancient truths and laws,

stories of loyalty and torture.

There is no way you can rest,

you have to swallow this, gulp it down

though you arc already choking

and your car is exhausted.

You are unable to interrupt me

or say anything in return;

my time has arrived

and I insult you, curse you,

you impostor, poisoner,

desecrator, slave, satan,

machine, death, death.

You swallow your shame

and are condemned to listen

not to speak,

because you are a monster

with only ears

and a bellyful of treason;

no tongue or truth,

you are helpless, can call me neither weakling

nor powerful,

cannot utter words like “grace” or “despair,”

shout to me to stop

though you are burning with slavish rage.

I greet you, crippled creature,

am glad you are here

immured day and night,

you cursed extension of the Great Suspicion,

the diabolical belly of inhuman force

which is so feeble that it shudders day and night.

Now you evoke my power

my unified an undivided power,

I cannot plant someone else

in my place

I am who I am —

restlessness and searching,

sincerity and pain,

faith, hope, love,

your magnificent counter-suspicion —

you never can divide me,

make me your double,

catch me

lying or calculating.

You’ll never be the executioner of my conscience,

you don’t have a choice

bill to swallow my joy

or, at times, my sadness.

You, my enemy,

my infertile neighbor

so different and inhuman

unable to break loose

to become insane or to commit suicide,

I can tell

I wore you out,

your tail is between your legs

but this is only an outline.

of my revenge:

my true revenge

is a poem.

You will never know me,

your ears have no light,

will be hushed by the passage of time

while I am a tongue-flame

fire

that will never cease to bum

and scorch.

Translation: 1977, Sonja Kravanja

From: Embers in the House of Night

[Source: https://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/poem/item/5160/auto/Mikrofon-v-zidu]

Knuts Skujenieks:

To a Dandelion Blooming in November

If you know you must bloom

Don’t ask if the time has come

Don’t ask if the time has gone

If you know you must bloom

Heed the voice coursing in you

When sap disturbs your roots

When your greenness torments you

Heed the voice coursing in you

Lift up your yellow crown

Muddle plans and calendars

Muddle rules, muddle minds

Lift up your yellow crown

With you, we feel we are home

You bloomed unasked

You bloom unasking

With you, we feel we are home

[Source: Knuts Skujenieks: Seed in Snow. Lannan BOA Editions, 2016, translated by Bitite Vinklers]

[1] Source: https://www.marxists.org/archive/gorky-maxim/1934/soviet-literature.htm

Games