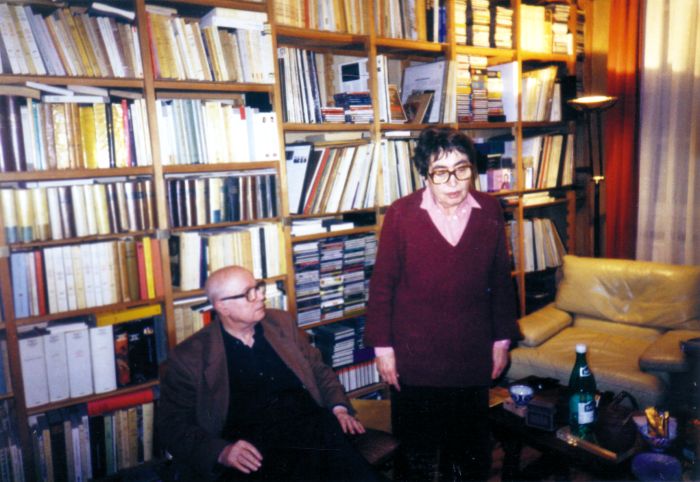

The Lovinescu–Ierunca Collection at the Central National Historical Archives (ANIC) in Bucharest is arguably the most important collection created by the Romanian Diaspora in Paris. The collection illustrates not only Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca’s interest in the subject of dissent in Romania but also how their activity at Radio Free Europe (RFE) created a transnational network of support for those who decided to speak against the regime.

Feature Film: Chelovek idet za solntsem / Omul merge după soare (Man Follows the Sun), directed by Mikhail Kalik, 1961, in Russian

Feature Film: Chelovek idet za solntsem / Omul merge după soare (Man Follows the Sun), directed by Mikhail Kalik, 1961, in Russian

The context of Khrushchev's Thaw allowed an unprecedented display of innovative filmmaking strategies in the case of the Moldavian SSR. Perhaps the most famous example of this “Soviet new wave” in cinematography – which received its name by analogy with the contemporary French movement of the “nouvelle vague” – was the feature film Chelovek idet za solntsem/ Omul merge după soare (Man Follows the Sun), directed by Mikhail Kalik, who had already left an imprint on the local film industry with a movie (produced in 1958) extolling the virtues of the medieval Moldavian “forest outlaws” (haiduks). In his new project, Kalik followed the emerging pattern of “poetic cinema,” intimately connected to the perceived liberalising tendencies of the Thaw era. Kalik himself later confessed that in this movie he found his own “language… the poetic language of cinema.” Based on a screenplay by Valeriu Gajiu, the film tells the story of a six-year-old boy who in one single day experiences numerous facets of life, from friendliness and help to heartlessness and rejection. It conspicuously lacked any elements of Soviet ideology and even made fun of the regime’s obsession with the stilyagi (members of a Soviet youth counterculture, active in the 1950s and early 1960s, mainly distinguished by “fancy” Western-style clothing and by their fascination with and imitation of Western lifestyles more generally). It is not surprising that the threat of Western ideological influences and ”contamination,” which was constantly on the mind of Soviet authorities on the peripheries, re-emerged in official rhetoric on this occasion. This film provoked the angry reaction of the Party leadership of the Moldavian SSR. Ivan Bodiul, the First Secretary of the local communist Party, sarcastically inquired: “Man follows the sun, and what does he see? He sees sheer nonsense, and not our Soviet achievements.” The authors of the film were summoned to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Moldavia and harshly criticised for their ideological deviations. The Second Secretary of the CPM, Evgenii Postovoi, who remarked that the movie could in no way “increase the corn crop in Moldavia,” was especially virulent: “What kind of movie is that? What do you show there? This boy is just running around… and he is walking toward the West, mind you.” Kalik was officially accused of “formalism”, while the local authorities banned the release of the picture. Only after Kalik personally smuggled the film to Moscow and showed it to the higher film authorities there was it allowed for public screening. The picture received highly positive reviews both in the Soviet and the foreign press and was critically acclaimed as one of the most original cinematic productions of the era, on a par with its best Soviet equivalents. However, both Khrushchev personally (who was apparently annoyed by a short erotic scene) and the Soviet dignitaries responsible for ideology were much less enthusiastic. Thus, the secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the chairman of the Party’s Ideological Commission, L. F. Il’ichev, observed during a meeting held on 26 December 1962 that, despite the director’s obvious talent, “there are serious flaws… in the movie. The search for a peculiar, unusual form degenerates, during several of the film’s episodes, into a purely external kind of originality, into mannerism and an uncritical imitation of foreign fashions.” The film was also discussed at the First Congress of the MUC in October 1962, where Kalik’s colleagues generally avoided open attacks and recognised the film’s artistic qualities, but nevertheless emphasised the director’s “mistakes” and talked about the movie in a highly reserved and ambiguous way. The only discordant voice was that of the visiting representative of the Ukrainian SSR, Navrotskii, who openly voiced the shock and surprise of the Soviet filmmaking community in connection with the film’s initial banning and the repressions against Kalik. This case is revealing concerning the constraints placed upon the artistic creativity of the filmmakers even under the most favourable circumstances of Khrushchev’s Thaw and the limits of the ideological non-conformity that the authorities were willing to tolerate. Although it remained one of Moldavian cinema’s major achievements, the movie was in fact banned again after Kalik’s emigration to Israel, in 1971, when his name was erased from the records of Soviet filmmaking. The movie was “rehabilitated” only during the Perestroika period.

The Hans Otto Roth Collection was officially registered and archived in the Archives of the Honterus Community in 1962, when it was officially included among the manuscripts preserved in this institution. The Archives of the Honterus Community, today known as the Black Church Archives had been established in 1958, following a law of 1957 regarding the functioning of denominational archives. This institution also received the archives and the old books held by the local parish of the Evangelical Church and by the former Honterus High School, an important cultural institution of Transylvanian Saxons starting from the sixteenth century. In 1974, when a large part of the archives in the possession of the institution was taken over by the State Archives on the basis of the archive law of 1971, the Hans Otto Roth Collection was protected against this nationalisation.Although the registers of the Archives of the Honterus Community from the 1960s prove that the Roth Collection officially entered in the possession of the institution in 1962, it is difficult to retrace the circumstances in which this event happened and who was in fact the donator. Thomas Șindilariu, a historian and archivist who works for the institution, believes that one of Hans Otto Roth’s acquaintances saved this collection and deposited it in Braşov after Roth’s arrest in 1952. Gustav Markus, the director of the Archives of the Honterus Community certainly had a key role in the acquisition of the Hans Otto Roth Collection, for this event would not have been possible without his official approval. He assumed a significant risk in including this collection created by a former political prisoner among the records of the institution he administered at a time when political repression in communist Romania was not yet over. Besides, Hans Otto Roth’s children, Herbert and Marie Luise, had been sentenced for political crimes in the so-called Black Church Trial only four years earlier.Klaus Popa, who edited part of the documents in this collection, asserted that Roth himself had a crucial role in the preservation of his own archives, for he deliberately sent part of his documents to Brasov and other parts to Sibiu and Cincu (Braşov county) in order to protect them from the Securitate. In order to support this assertion, Klaus Popa invoked certain notes made by Roth on the folders with documents in the collection marked “Kr.” (Kronstadt/Braşov) or “Gr.Sch.” (Groβ Schenk/Cincu) (Popa 2003, 10). This remains only a hypothesis because the Cincu church archives include no part of Hans Otto Roth’s personal archive.

Roger Loewig created the painting “Noch tönt Gesang unter der zerbrochenen Brücke” [There is still chant under the broken bridge] (oil on hardboard, 59,5 x 79,5 cm) in 1962. Loewig was no stranger to avant-garde and abstract arts, to which he was extensively exposed during his museums and gallery visits in West Berlin throughout the 1950s. Yet the artist was in his early years rather fascinated by fauvism and expressionism. The motifs of his paintings were similar to his drawings and lithographs. Starting mid-1960s Loewig gave up on painting, strongly conditioned by economic and space scarcity, focusing rather on drawings and lithographs. The painting was re-framed by the artist during the 1990s when a poem was added, together with a third sheet from the lithography series 'Welke Wege' [Fading paths] from 1970, added in the lower part of the framing. These lithography series belongs to the lithographs created illegally together with Willi Negrazius, who held a position in the printing ateliers of the Fine Arts School Berlin Weißensee.

'Welke Wege' [Fading paths] together with the series 'Mein Mund webt ein Fangnetz für den Tod' [My mouth weaves a catch net for death] have been eventually published in 1971 together with the publishing house Steintor in Hanover, shortly before Loewig's departure from the GDR. These can be accounted among the last lithographs series created by the artist while still in the GDR. The painting belongs to the artworks confiscated by the Stasi, being among the few that was returned to the artist. It was also included in a series of exhibitions, amongst the most recent 'Roger Loewig-auf der Suche nach Menschenland' [Roger Loewig-on the path towards a people's country], organised in 2000 in Museum Nicolaihaus der Stiftung Stadtmuseum in Berlin, celebrating the tenth anniversary of the German reunification.

The triptych M.K. Čiurlioniui (M.K. Čiurlionis [1875-1911] was a famous Lithuanian artist and composer) was created in December 1962, at exactly the same time that the leader of the USSR Nikita Khrushchev criticised the Second Exhibition of Modern Art in the Manezh Gallery in Moscow. Following this ideological campaign, the artist Antanas Gudaitis (1904-1989) was criticised in Soviet Lithuania. He was blamed for deviating from Socialist Realism. While no actual works by the painter were mentioned during this ideological campaign, Gudaitis himself believed that it was because of his triptych (see Lubytė, E. 1997, Tylusis modernizmas Lietuvoje [Quiet Modernism in Lithuania], Vilnius, p. 88).

The anthological exhibition of Ivan Picelj was held at the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb in 1962. On that occasion, Tošo Dabac took a series of photographs as a memento of the event. Six years later, in 1968, Dabac had his exhibition in the same place, and on that occasion Picelj made a poster for it.