Croatian scholars made important contributions to the work of the Pugwash Movement by gathering primarily around the Institute for the Philosophy of Science and Peace of the Yugoslav (after 1991 Croatian) Academy of Sciences and Arts (JAZU/HAZU). In 1966, a group of Croatian intellectuals from the Institute, led by Ivan Supek, in 1966 launched the journal Encyclopaedia moderna: časopis za sintezu znanosti, umjetnosti i društvene prakse. It was published in all Yugoslav languages and dialects, but there were also articles in English. In addition to the central editorial office in Zagreb, it had editorial staffs in Belgrade, Ljubljana, Sarajevo, Skopje and Titograd. It was issued quarterly, although occasionally deviated from this schedule. The editor in chief was Ivan Supek (except in 1975, when the editor was Eugen Pusić). Since the mid-1980s, Supek was assisted by Nikola Zovko and Bojan Marotti (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

As a multidisciplinary journal, it promoted universalism and a humanistic orientation for science and the arts, as well as the complete disarmament and the creation of world peace. The first issue began with the “A Word from the Editors,” in which they stress: “we stand between military, economic and ideological blocs, and it is clear that in the event of a [global] conflict there can be no victory, but only a general disaster” (p. 1). They insisted on the universality of humankind: “Although the world is so fatally disunited, in every corner of it peaceful, humane and progressive thought is smouldering" (p. 3).

The goals of the journal were almost identical to the goals of the Pugwash Movement, and Supek insisted that every issue must contain something about the movement. “Pugwash” or “Peace Studies” or some column with a similar name was published in almost every issue. It would usually convey information, documents, declarations, or reports from Pugwash Conferences and other meetings. All of the contributions in the column were in English, in attempt to make the journal accessible to international scientific currents.

In the 1960s, Encyclopaedia moderna was relatively popular due to the prominent intellectuals who contributed articles to it. The journal strived for academic freedom and was even open to topics that the communist government considered undesirable, as was the case with religion (Kolarić 1973). The Yugoslav communist authorities did not like such intellectual independence, and the government reduced the funding for all of Yugoslavia's Pugwash organisations and publications. In 1976, Encyclopaedia moderna was forced to shut down because the government completely severed its funding (Knapp 2013, 99). In the 1980s, the very existence of the Pugwash organisation in Yugoslavia was questionable, mainly because Supek was out of favour with the communist regime. Still, the movement survived those trying years.

The journal was re-launched after the fall of communism in 1991, with Nikola Zovko as editor-in-chief, but its scope was oriented more towards Central Europe. It was published until 1998, and Marotti believes the journal was "naturally extinguished" because the themes of the journal were no longer as current as during the Cold War (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

After his first attempt at sewing and displaying a Romanian flag was thwarted by his wife, on 12 June 1966, Muruziuc planned his next action more carefully, endowing it with a powerful symbolic significance. He made the flag himself, in his own shed, on 27 June 1966. He bought 2m of red cloth in the village shop on 26 June, while the blue material (1m) was acquired at the shop in the neighbouring village of Alexăndreni. Muruziuc used an old bed-sheet for the yellow portion of the flag. According to a later examination carried out by the KGB, the flag was 2m 57cm long and 78cm cm wide. Muruziuc claimed that nobody witnessed his work on the flag. Early the next day, he entered the territory of the factory, climbed the chimney, and fixed the flag on the building’s lightning rod, so that it was visible throughout the village. After Muruziuc’s arrest, the flag was confiscated by the KGB, and served as an essential piece of incriminating evidence during the trial. This was apparently the first case of the public display of a Romanian flag on the territory of the MSSR after 28 June 1940. The flag was destroyed by the KGB staff on 13 January 1967. This photo is the only remaining record of the flag made by Muruziuc.

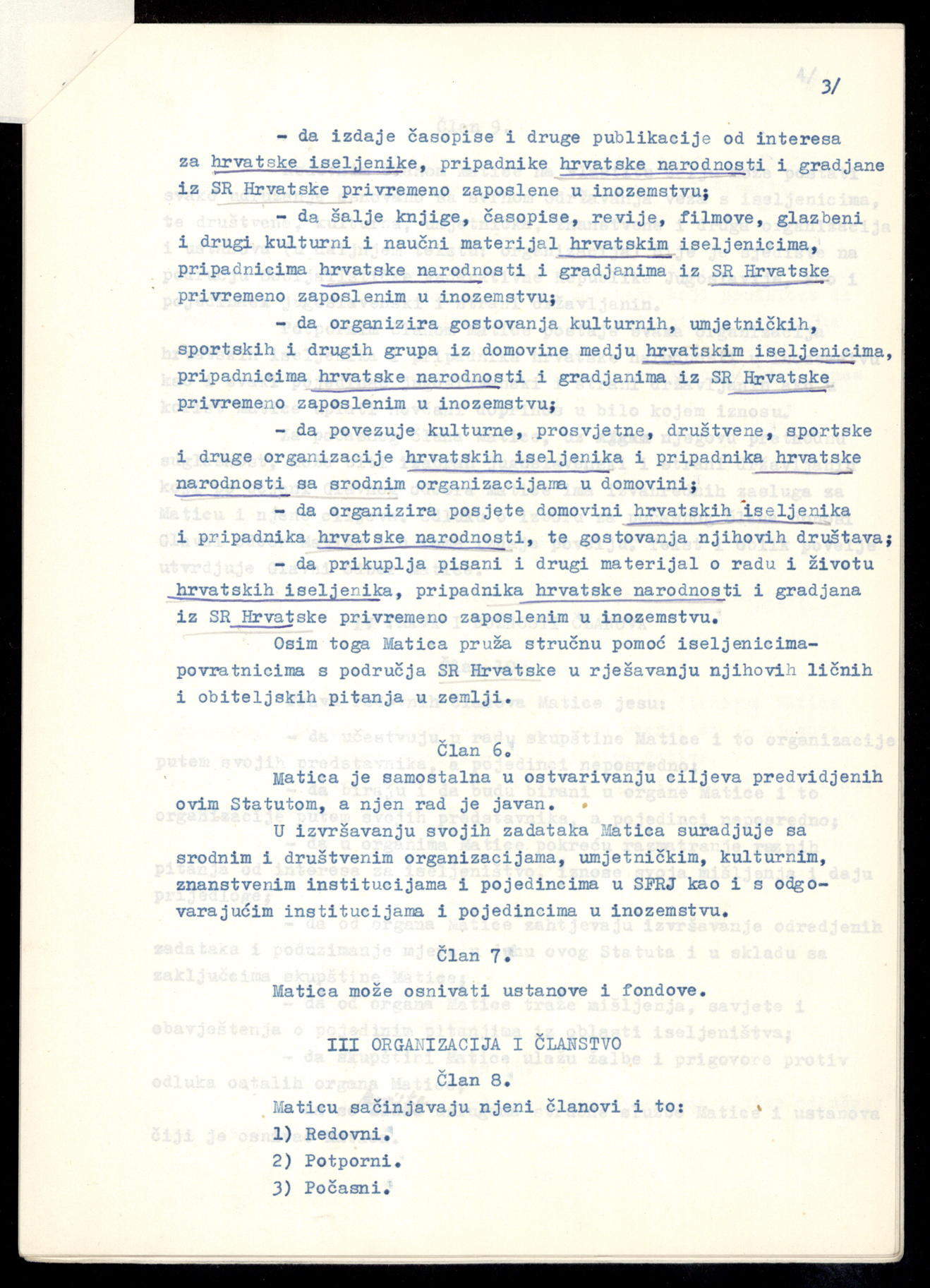

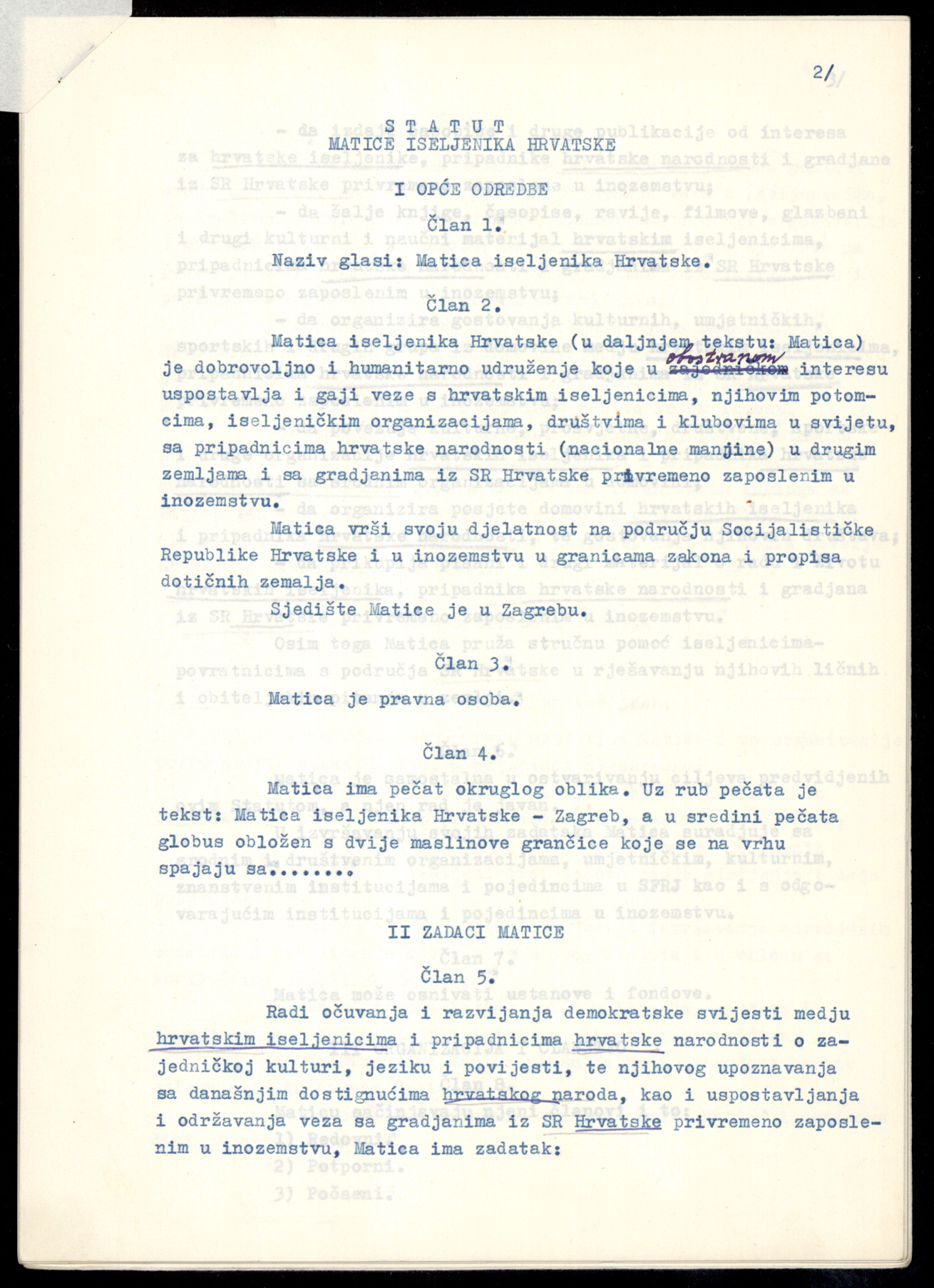

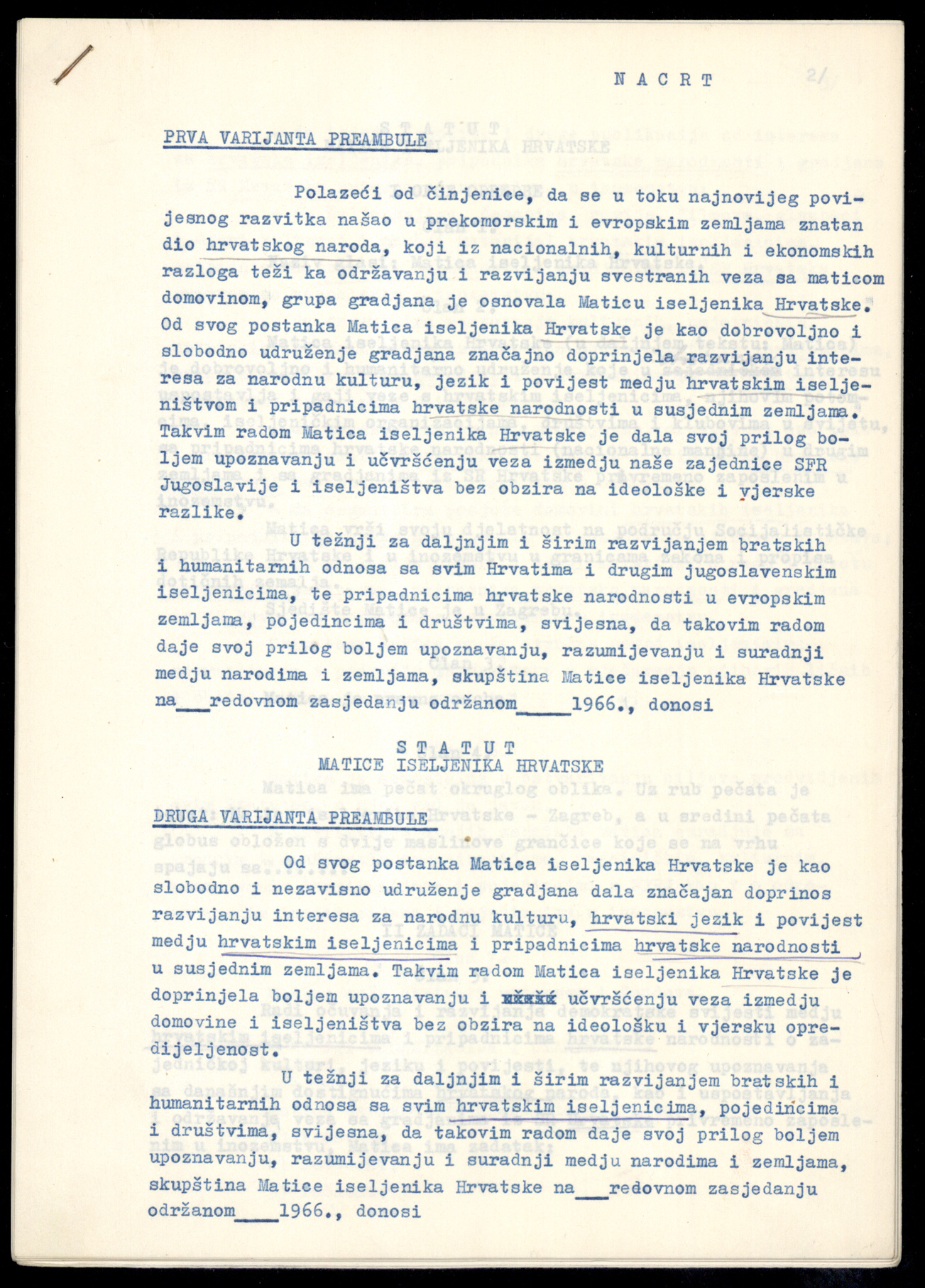

This document is one of the reasons for the political fall of Većeslav Holjevac, the president of the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (EFC), because it led to charges of his nationalist activity. The members of the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the EFC faulted the Charter’s text for its frequent emphasis on national adjective ("Croatian people," "Croatian language," "Croatian emigrants," "Croatian nationality") over the more accepted terminology ("emigrants," “our emigrants,“ “emigrants from Croatia," etc.).

Namely, the communist government did not support this emphasis on national qualities; rather it resolved the national question in heterogeneous Yugoslavia by imposing the "supranational" ideology of "fraternity and unity," which was supposed to act as an integrative factor. Consequently, cultural institutions were not allowed to carry the name "Croatian" but rather ”of Croatia.“

By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archives of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute for Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

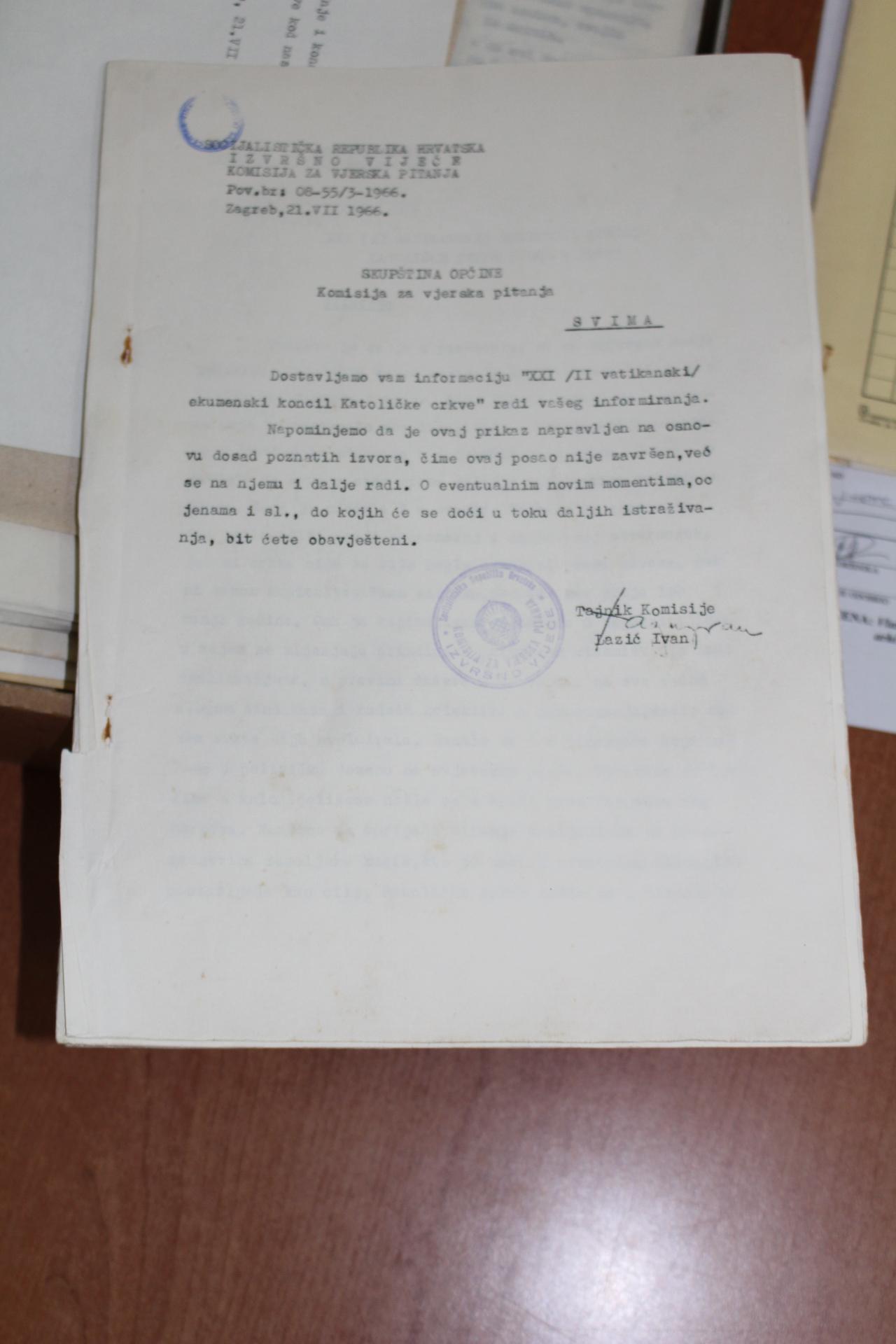

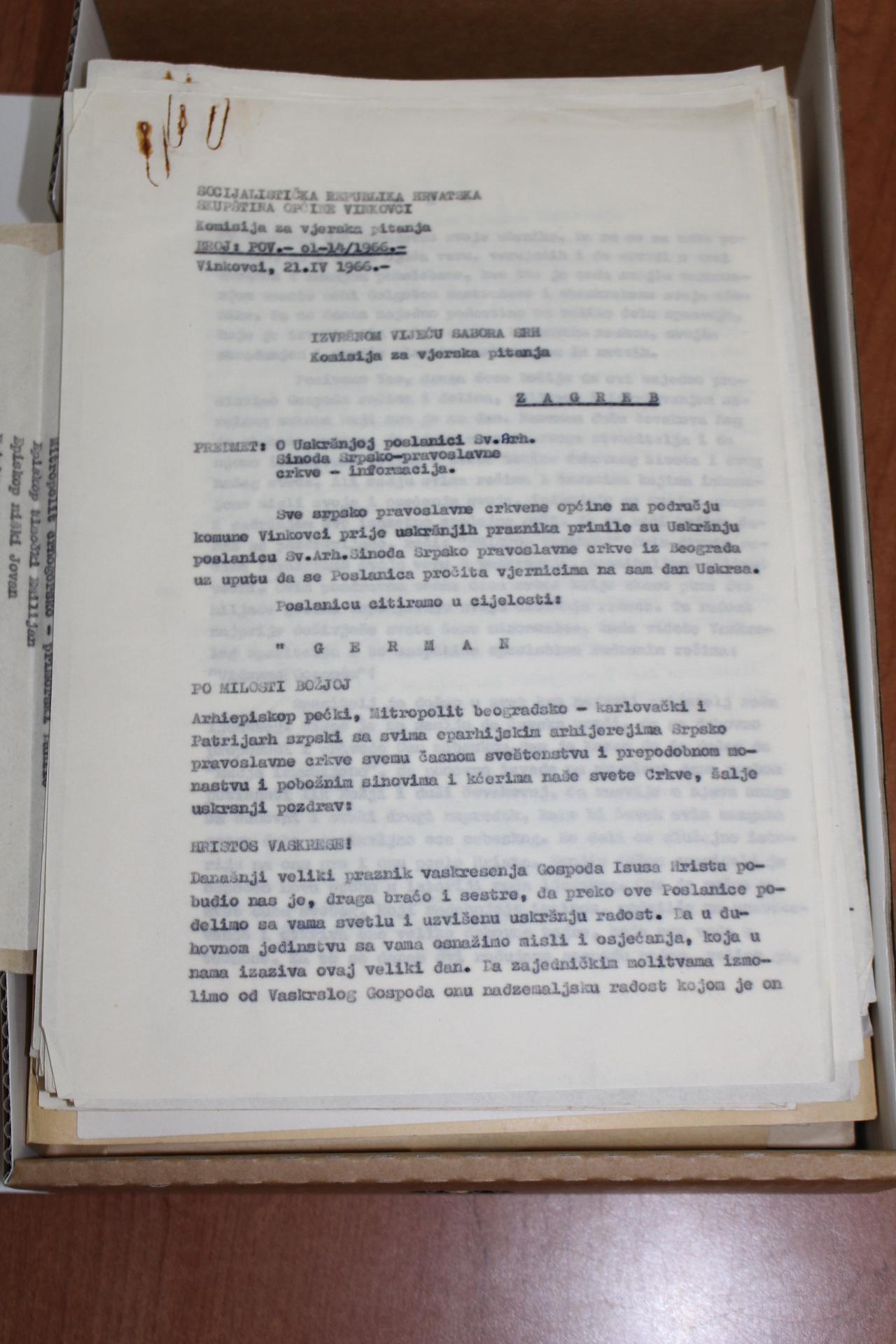

Izvještaj o Uskrsnoj poslanici Svetoga arhijerejskog sinoda Srpskoh Pravoslavnoj Crkvi, na hrvatskom, 1966. godine

Izvještaj o Uskrsnoj poslanici Svetoga arhijerejskog sinoda Srpskoh Pravoslavnoj Crkvi, na hrvatskom, 1966. godine

The letter of the Commission on Religious Matters of the Vinkovci Municipal Assembly to the correspondent commission at the republic level on the activities of Serbian Orthodox Church at the time of Easter in 1966 contains the entire epistle that was read in all Orthodox churches in the Vinkovci Municipality. This was an example of how the regime also attempted to exert control over the Serbian Orthodox Church by collecting the information on almost all of its religious activities. As a religious institution, the Serbian Orthodox Church was also regarded as a source of anti-socialist policy. “In addition to increased activity by the Roman Catholic Church, we may also notice in the Orthodox Church a growing activity, which can be seen in the number of believers, organisational arrangement, the formation of ecclesiastical associations and the new religious buildings,“ it says in the letter.

Following Mihai Moroșanu’s arrest in late July 1966 and his subsequent trial, the sentence in this case was issued on November 2, 1966. As in other similar instances, the text of the sentence carefully summarised Moroșanu’s misdemeanours and “crimes” against the Soviet order. According to this document, his record of open opposition to the Soviet regime could be traced back to his student years at the Polytechnic Institute. Even before his expulsion from the institute in October 1964 due to his involvement in the laying of a floral wreath to Stephen the Great’s monument, he allegedly displayed “un-Soviet” behaviour. Thus, according to the testimonies of several among his fellow students, Moroșanu “systematically and purposefully distorted Soviet reality; openly, in the presence of other students, expressed his discontent with the existing order within our country, and frequently made pernicious and tendentious statements concerning different questions of the economic and cultural development of the MSSR.” While these general accusations were serious enough from the authorities’ point of view, they paled in comparison with his nationalist views. Moroșanu was accused of “impersonating an alleged defender of ‘Moldavian national culture and art’” and, most importantly, of “purposefully conducting propaganda of his ideas, [which were] filled with a nationalistic and chauvinistic content, being directed at fomenting enmity and hostile relations between different nationalities.” The document is quite revealing in connection with the personal roots of Moroșanu’s opposition to the regime. His “anti-Soviet” attitude was allegedly triggered by his family’s deportation and particularly by his father’s arrest and conviction to seven years of forced labour in 1949. Moroșanu’s family background appeared as especially untrustworthy not only because of their identification as “kulaks,” but also because his father purportedly “was a leader of a sect of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which had an impact on Moroșanu’s education.” Apparently, his activities intensified starting from the summer of 1963, when, during a discussion about the poet Evgeni Evtushenko, he was trying to convince his colleagues that the Soviet press was “lying.” On this occasion, he also displayed “hatred” toward Communists. More ominously, Moroșanu “propagated ideas of a nationalistic and chauvinistic character among students, demanding that his colleagues speak only Moldavian to him.” He also openly condemned the placing of Lenin’s statue on the main city square, arguing that Stephen the Great’s monument should replace it. Thus, the incident involving the ceremony at the statue was construed as the culmination of numerous instances of nationalist-inspired acts on Moroșanu’s part. The sentence justified the decision to expel Moroșanu from the university. However, it also emphasised that, during his stint as a worker at the reinforced concrete plant in Chișinău, had Moroșanu continued his hostile propaganda activities. Citing several witness accounts, the court concluded that these acts aimed at ”fomenting racial and national hatred among the plant’s workers.” Concretely, he was accused of openly voicing his views that “in the Moldavian SSR everyone should speak only Moldavian, [that] all the official signboards and inscriptions should be writtenonly in Moldavian, that the Moldavian language should use only the Latin script, because it belongs to the group of Romance languages, and thus the Russian alphabet is foreign to the Moldavian language, and that persons of ‘non-Moldavian’nationality do not have any right to work in Moldavia if they do not speak Moldavian.” To compound the picture, Moroșanu allegedly displayed anti-Russian tendencies and occasional anti-Semitic behaviour toward his co-workers. He also condemned the redrawing of the Bessarabian borders in 1940, when the northern and southern districts of this region were transferred to Ukraine, while the rest of Bessarabia was merged with the MASSR to form the new MSSR, arguing that these were Moldavian lands “occupied by Russians” and “illegally transferred to the Ukrainian SSR.” In this context, it is not surprising that the incident in the Chișinău shop on 28 July 1966 that led to his arrest was treated as a dangerous manifestation of “nationalism and chauvinism” and a serious breach of public order. This conclusion was in line with the increasingly intolerant attitude of the authorities toward any displays of “local nationalism” in the late 1960s. Moroșanu’s situation was undoubtedly aggravated by his refusal to admit his guilt and his persistence in the “mistaken and pernicious character of his views, oriented toward fomenting national divisions and hatred among persons of different nationality.” Moreover, he even “attempted to propagate these views during the entire judicial inquiry.” He only partially admitted being “wrong” incollecting the students’ signatures to protest against the relocation of the statue. His stubborn refusal to bend to his accusers’ wishes and his failure to “repent” were taken into account by the court’s final sentence, which emphasised the “particular seriousness and social danger” of the “crime” allegedly committed by Moroșanu. Despite his physical disability, on 2 November 1966 the defendant was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment, on the basis of Article 71 (undermining the national and racial equality of Soviet citizens) and Article 218 part 1 (hooliganism with aggravating circumstances) of the Penal Code of the Moldavian SSR. The material evidence in the case was deemed “without any value” and subsequently destroyed. Moroșanu’s sentence is revealing for the “hierarchy of dangerous behaviour” constructed by the Soviet authorities in this period. Local nationalism was clearly one of the most condemnable forms of opposition to the regime, especially on the Soviet periphery.

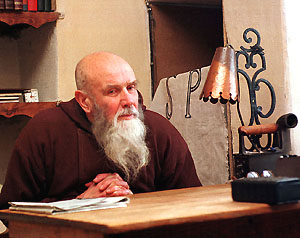

Having been sent to the provinces of Lithuania in 1966, the ex-Soviet political prisoner and Catholic priest Fr Stanislovas made Paberžė an attractive place for the intelligentsia and people who shared non-Soviet attitudes. Fr Stanislovas became widely known in Lithuania for his deep sermons and his ability to attract and engage people through various initiatives, like collecting, repairing and restoring old things, his philosophical attitude towards things (similar to that of Rainer Maria Rilke), and the importance of activity. The items (material objects) in the collection are a testimony to the environment in which the cultural opposition led by Fr Stanislovas discussed political, religious and social issues during Soviet times.

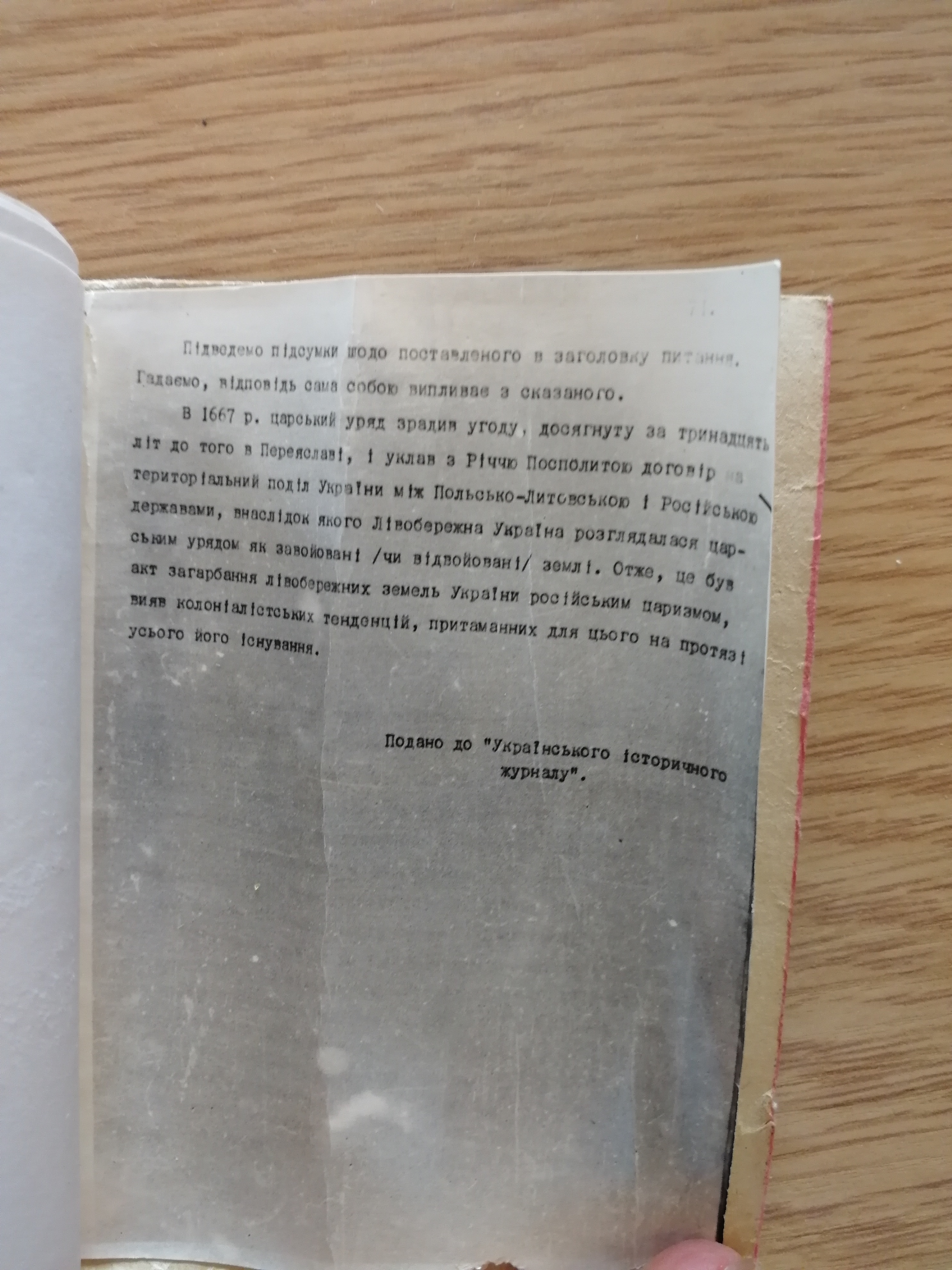

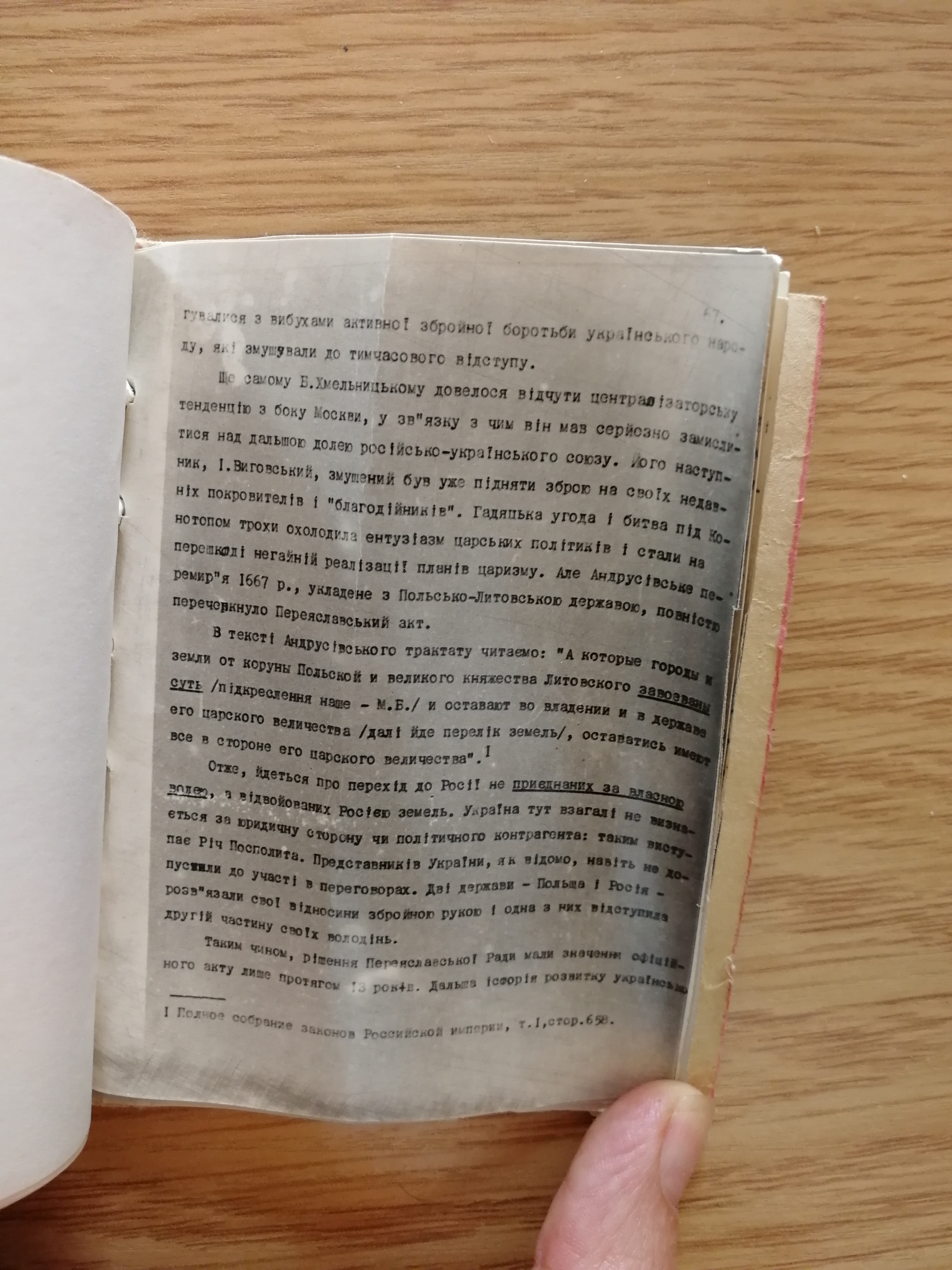

This samizdat miniature with its photocopied (from a microfilm) and manually bound pages represents a typical form of smuggling underground materials from Soviet Ukraine. Microfilms and miniature forms were the only way to safely smuggle abroad illegal literature and documents from the Soviet Union.

This samizdat book was rolled and hidden in a luggage of a Smoloskyp courier. This was the way how Smoloskyp couriers managed to smuggle many other Ukrainian samizdat and dissident materials, including Bil’mo by M. Osadchyi, O. Berdnyk’s manuscripts, the entire collection of the documents of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, D. Shumuk’s memoirs, a photo collection belonged to M. Rudenko, and so on. The obtained materials were later published in both Ukrainian and English, and were circulated in international media.

Mykhailo Braichevsky wrote his article Priednannia chy voz’ednannia? (Annexation or Reunification?) in 1966 in which he openly criticised the Theses on the 300th Anniversary of the Reunification of Ukraine and Russia (1654-1954), a document imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1954 as the only permitted interpretation of the events of 1654 in Ukrainian history, namely, the Pereiaslav Council and the Treaty of Pereiaslav, after which Ukraine became a part of the Russian Empire. Braichevsky’s work was circulated in samizdat in Ukraine, smuggled abroad, and was published in Canada as a brochure. As a result of this writing, Braichevsky was fired from the Institute of History, where he worked as a researcher. In the next decade he was oppressed by the Soviet authorities and the Communist Party that demanded his public “repentance” and acknowledgment of his research “falsities.” He was not allowed to officially continue his research career.

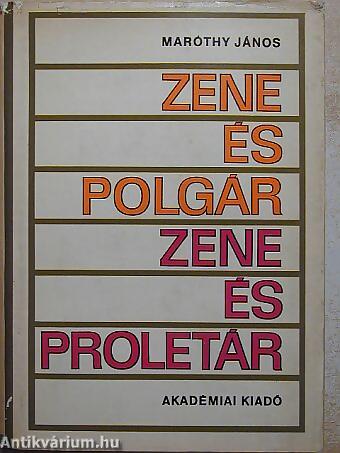

![Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book](/courage/file/n35318/marothy-janos-zene-es-polgar-zene-es-proletar-842907-nagy.jpg)

Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book

Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book

There were changes in the history of Hungarian scholarship on music in the 1960s. Researchers started to analyze the personal and collective dimension of the reception and to think about how the historical past could be interpreted through popular music.

The two symbolic dates were 1962 and 1966. In 1962, József Ujfalussy’s book A valóság zenei képe [The Musical Image of Reality] was published, in which he examines the texture of the music and the places and ways in which it was presented. In 1966, János Maróthy’s major work, Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletarian], was published. In his book, he elaborated on the different types of music in the twentieth century. He studied the relationships between the bourgeois worldview and bourgeois music, as well as connections between the folk song and bourgeois music forms and historical types of the folk song. In his book, Maróthy dedicated a section to the relationships between folk and mass music, emphasizing the music of the workers and trying to examine the effects of folk music on workers’ culture. Maróthy turned away from the main directions of the local discussions on jazz. He was interested in the social roots of this type of music, its relationships to folk music, and its labor movement backgrounds. This book is one of Maróthy’s publications which had effects on later research methods.

Ernst Museum, Budapest, 16 April - 8 May 1966 One of the determining agents in the organization and history of the Studio of Young Artists was the board and the views represented by its members. After the election in 1964, artistic freedom and the integration of different tendencies became a priority. The board established a theoretic panel (for cultural-political reasons, the collaboration of artists and art historians earlier had not been nurtured or supported), and it encouraged members to be freer in their expressive experiments.

Negotiating with the ministry (and personally with the main cultural political decision-maker, György Aczél) the chairperson, István Bencsik, received permission to hold a “jury-free” exhibition (which meant that only board members would select the works due to spatial limitations). This “yearly exhibition” was the first to display non-figurative works, which were on exhibition in a separate room (with a surrealist and a pop-section as well).

The exhibition became a huge professional and popular success, so they planned the next “yearly exhibition” in the same manner. However, an inner conflict (to put it simply, the antagonism between the abstract and figurative artists) grew into a major political scandal due to a denunciative letter sent to the authorities by some of the board members. As a result, the 1967 exhibition was decimated by a rigorous “outer” jury. Board members were dismissed by the authorities, and the artistic director was fired and even banned from the profession.

Between 1964 and 1975, employees of the Museum of Folk Techics in Sibiu rescued five windmills from Dobrogea, which were at risk of being destroyed by the communist regime’s agricultural modernisation drive following the completion of collectivisation in 1957. A key role in this endeavour was played by Hedwig Ulrike Ruşdea, a museologist working at the museum, who in the mid-1960s specialised in pre-industrial Romanian windmills. The Museum's team not only rescued and reassembled windmills in its open-air exhibition, but also conducted extensive research on their history and on their social and economic role within the communities, and collected stories told by local inhabitants about windmills and their former owners. Ruşdea later wrote several academic papers on windmills from Dobrogea based on her research findings. Some of them, such as “Morile de vânt din Dobrogea – România: Descriere şi tipologie” (Windmills of Dobrogea – Romania: Description and Typology), are available in manuscript in the scientific archives of the ASTRA Museum. After a short introduction to the history of windmills in Romania, Ruşdea discusses in this paper their evolution in Dobrogea and notes the devastating impact that the region’s rapid economic modernisation had on these essential artefacts of the cultural heritage of the region. While in the early twentieth century there were over 740 windmills in the region, by the beginning of the 1980s their number had decreased to only three. In addition, the study presents a typology of windmills according to structure and operating principles, and compares windmill technology in Dobrogea with that in other parts of Europe.

Čolak, Nikola. Struggle goes on: independent Yugoslav intellectuals are not surrendering, in Italian, 1966. Manuscript

Čolak, Nikola. Struggle goes on: independent Yugoslav intellectuals are not surrendering, in Italian, 1966. Manuscript

The collection documents the work of Croatian historian and political émigré Nikola Čolak (1914-1996). In 1966, he belonged to a group of academics and thinkers from Zadar, who officially sought to break the Communist Party's monopoly on truth by establishing the first journal not controlled by the Party. After the suppression of this initiative, Čolak was forced into exile in Italy. The so-called Movement of Independent Intellectuals represented the first attempt to create a formal cultural opposition circle not only in Croatia, but in Yugoslavia as a whole, which is recorded through this collection.