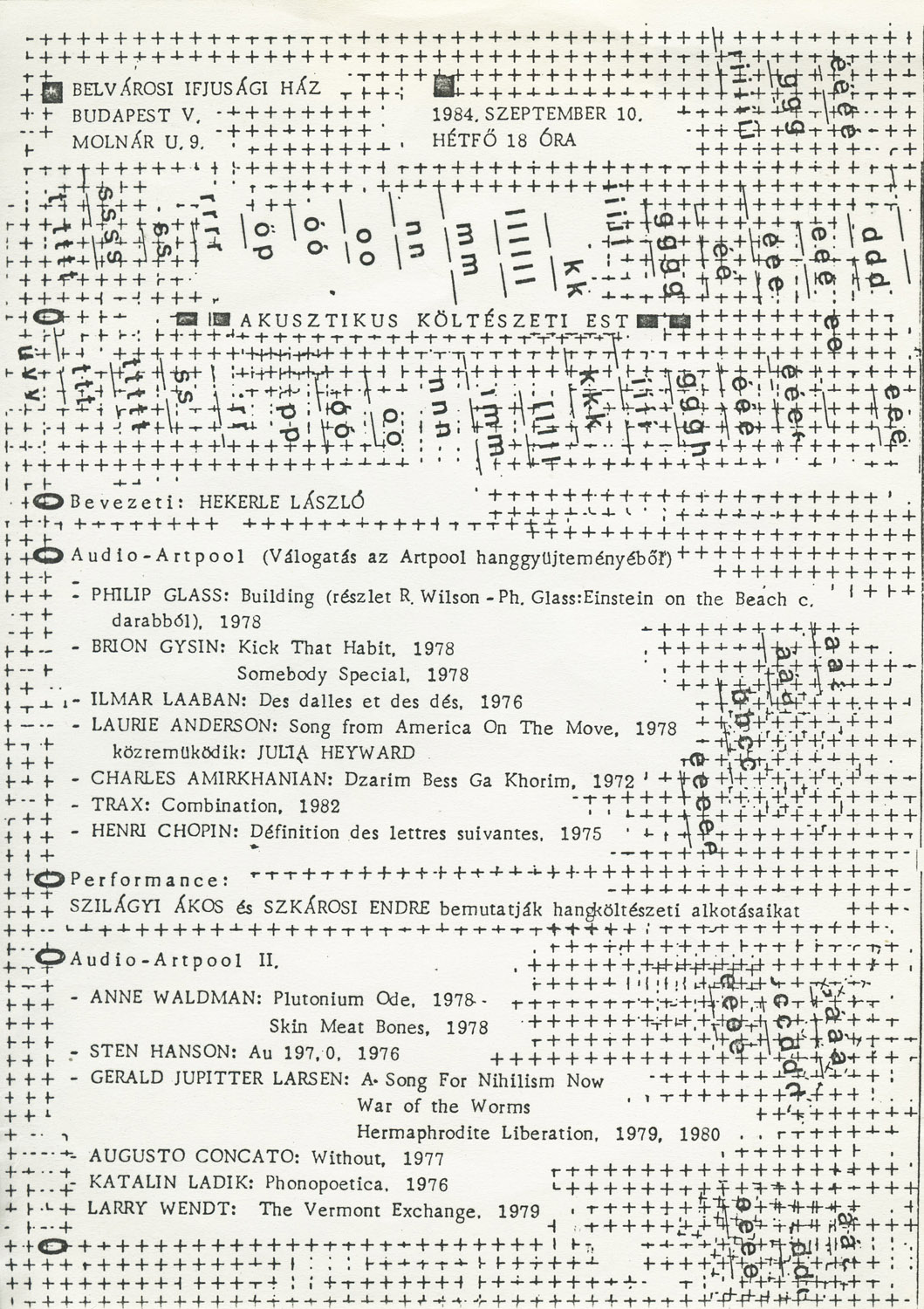

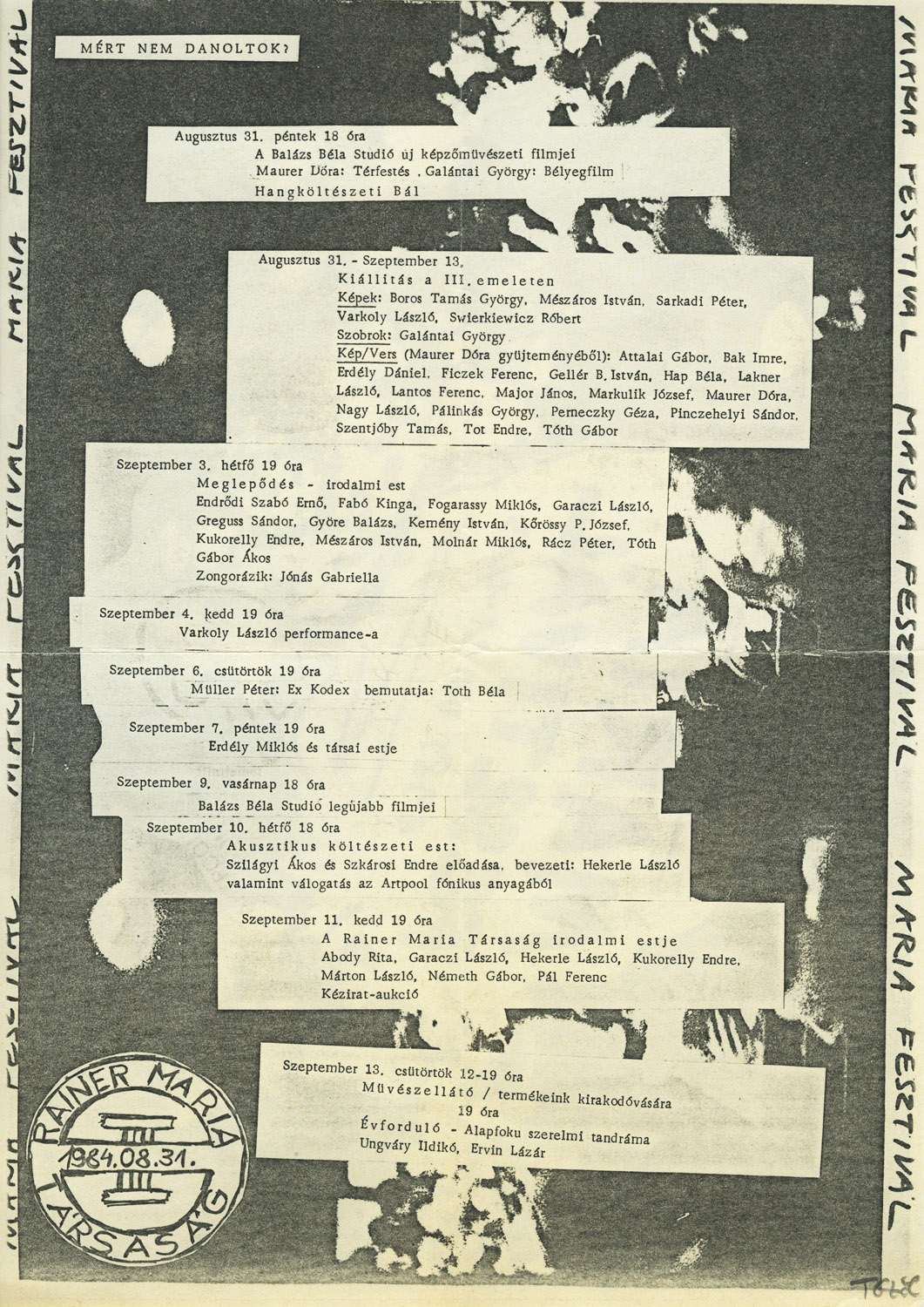

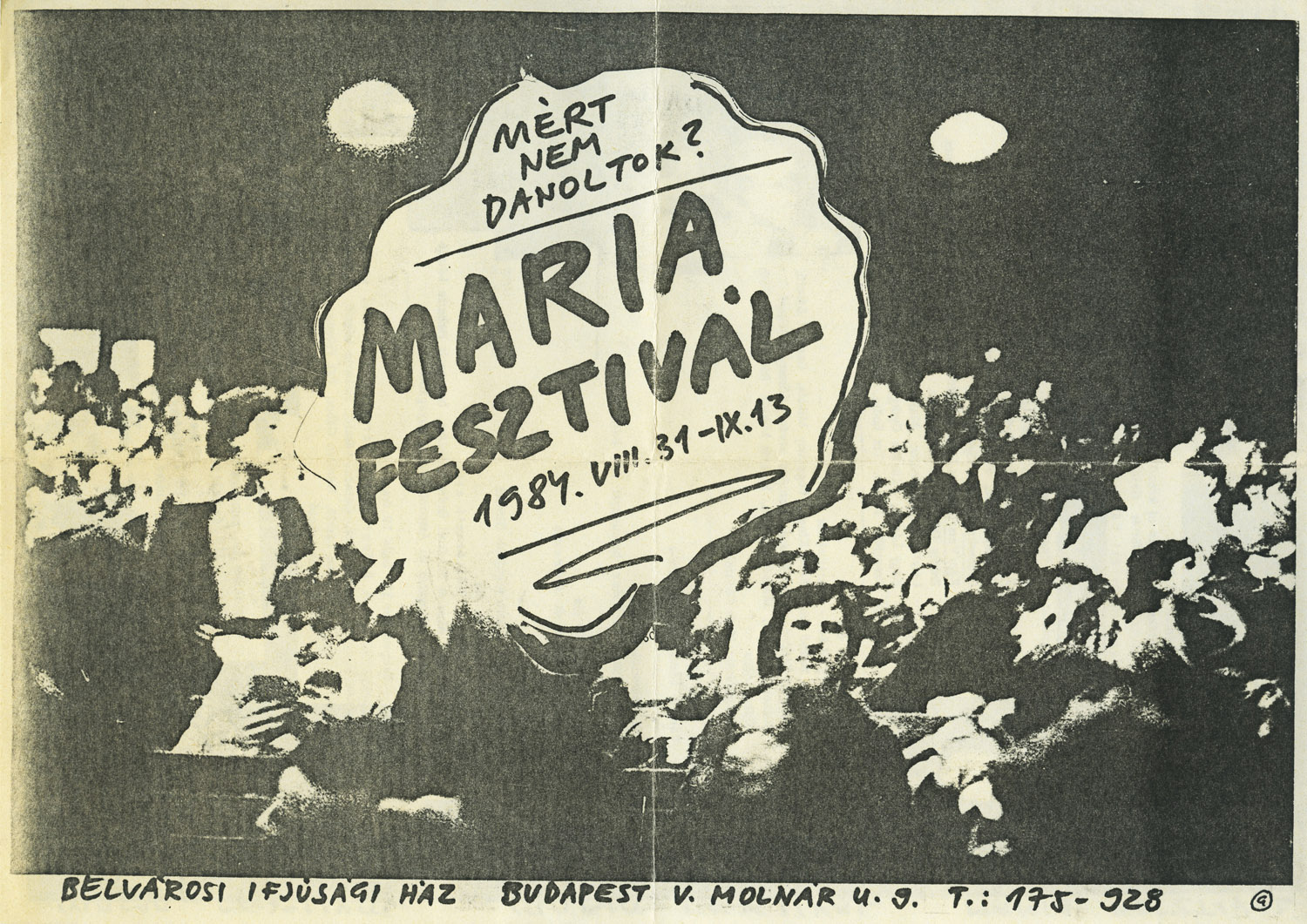

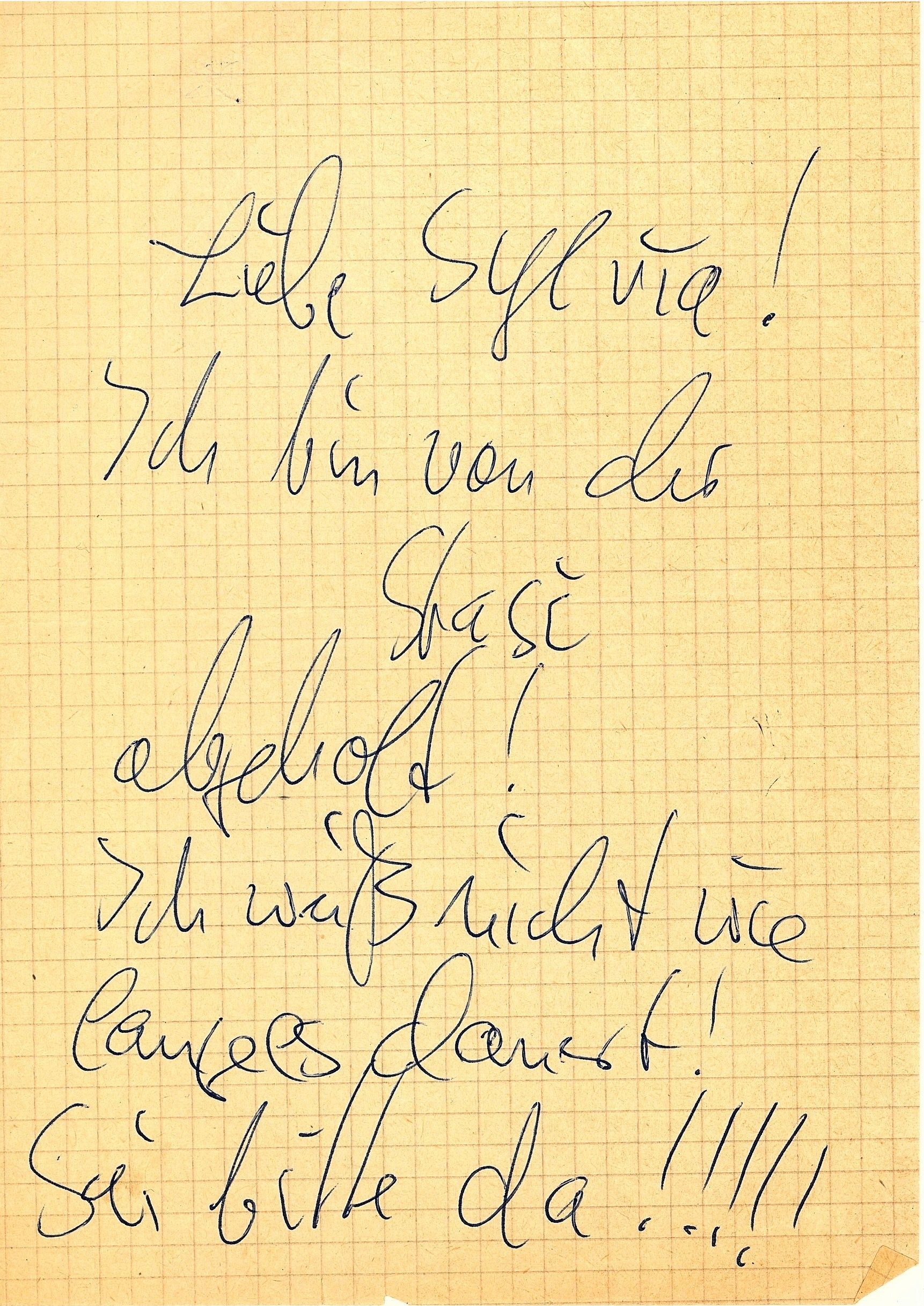

Scrisoarea „trecută ilegal” peste granița româno-maghiară, în limba maghiară, 6 octombrie 1984 (dimensiunile scrisorii: 15 cmx14cm)

Scrisoarea „trecută ilegal” peste granița româno-maghiară, în limba maghiară, 6 octombrie 1984 (dimensiunile scrisorii: 15 cmx14cm)

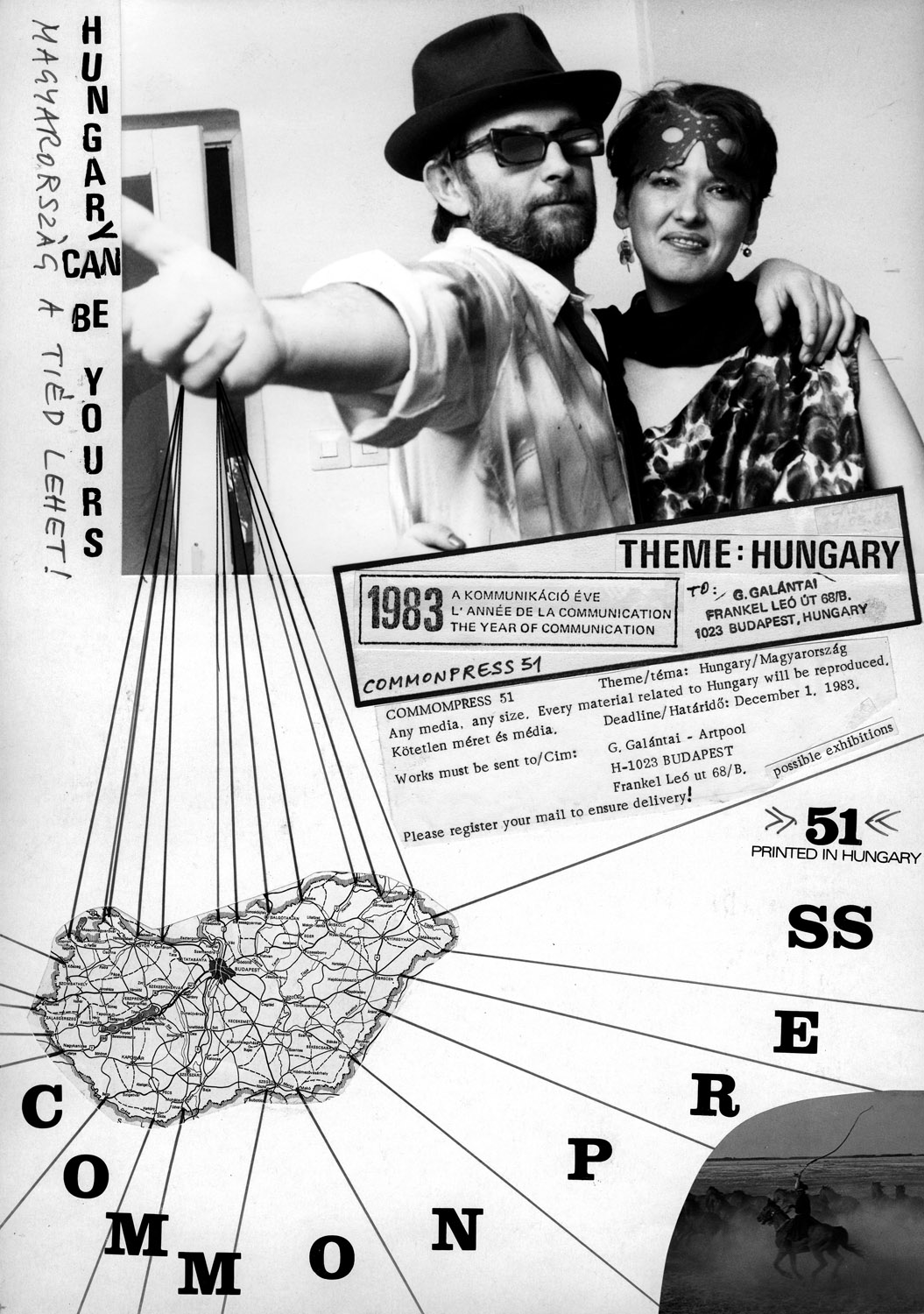

The Ellenpontok – Tóth Private Collection includes several hundred letters dating from that time. Especially interesting are the letters and notes of various shapes and sizes, smuggled primarily across the Romanian–Hungarian border by individuals during the eighties. In that time the relevant Transylvanian events had news value. Measures taken against the Hungarian minority were hardly talked about in the press, so it was essential to spread information to the broader public, partly with the purpose of protecting the victims of such measures, and partly in the hope that the situation of the minority would be improved by drawing the attention to these atrocities occurring under the Romanian communist regime.

This smuggled letter, size 15 cm x 14 cm, was delivered to the Tóth family in October 1984 while they lived in Budapest. The senders were the Spaller couple, old friends of the Tóths living in Oradea. Both Árpád Spaller and his wife Katalin obtained their degrees at Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, in 1970 and 1971 respectively, in special education (health pedagogy) and Romanian language and literature. After graduating they both worked as teachers in Oradea (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

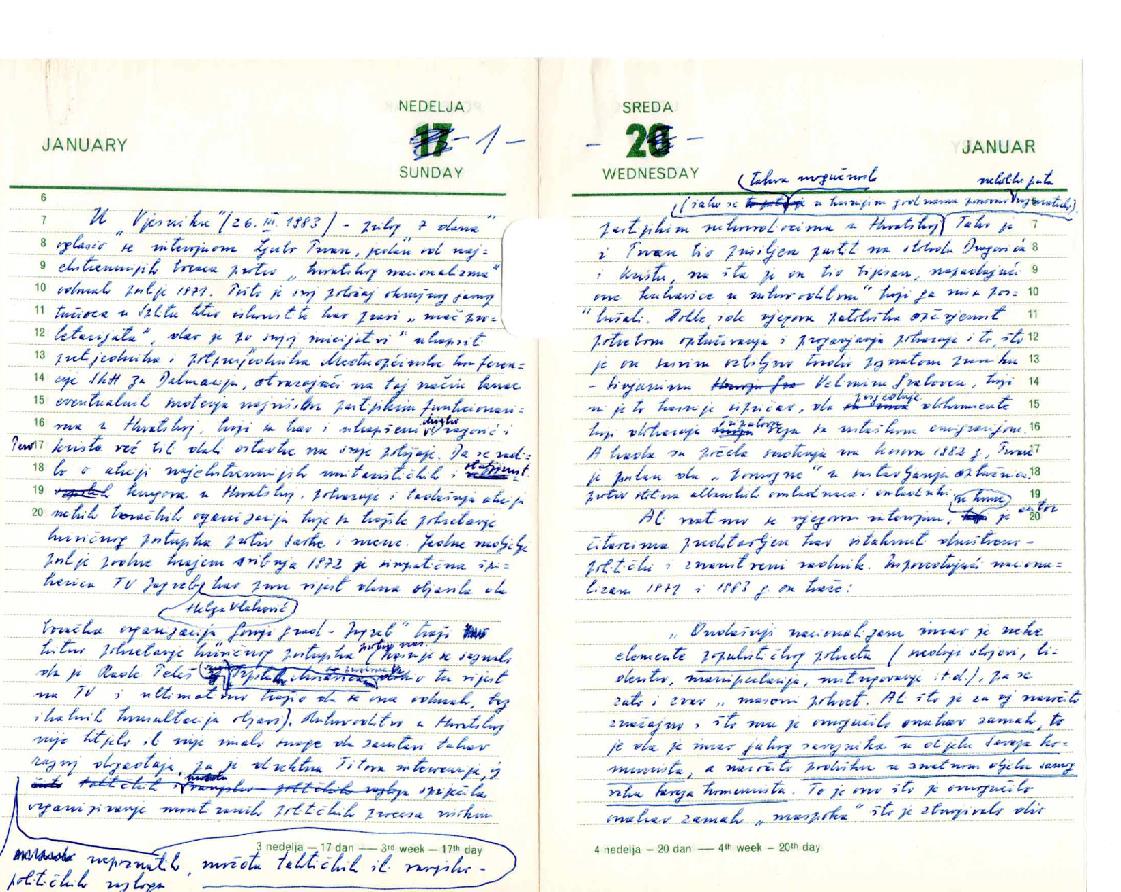

The text of the letter is as follows:

”Dear Ica, Karcsi and Zsuzsika!

Excuse us for not having written so far, although we were glad to receive your postcard. The truth is that we hesitate to even send a postcard for fear we might end up like Kati Gyulai [Gyulai Katalin, verse performer from Oradea (Molnár 1993)], who underwent a thorough customs control only to be refused entry to the country. Quite an unfortunate case. On the other hand, they keep a close eye on us and they mean it seriously. They keep harassing people. Árpi Varga, [Árpád Varga, 1951-1994 (Sipos 1995)], that miserable historian from Tileagd was also threatened. They also showed up in the home of Sófalvi, that photographer from Satu Mare who took photos at the Literary Round Table, and confiscated some of his films and books. We have no idea when this will end but we ought to be cautious.

Unfortunately, we were denied entry to Hungary. We were informed about this in September, although the decision was already made in June. So, we can apply again next June. Unfortunately, we cannot expect much. The help from our acquaintance hasn’t been efficient which doesn’t surprise us. We do not have any other contacts to turn to, so applying under such circumstances is totally pointless. Do you happen to know anyone influential who could help us? To be honest, it would mean a lot to us now, because we are rather disappointed. We would appreciate your help.

Otherwise, everything is the same. We are working and living from one day to the other. Endre attends school, he pretty much needs our assistance. The little one is growing. As for us, not much good news to tell. The Ady Circle is still active with the old members. Sometimes, when we have time, we also attend.

If you don’t mind we need to ask you to stop writing to us, or if there is anything important, address your letter to Péter Juhász [railway worker] Biharkeresztes MÁV station 4110. From time to time, we shall send you news about us. So, please don’t write directly to us. But please let us know how you are in a letter sent to the above address. And please be cautious in the case of the others, too.

With love, Árpi and Kati.

October 6, 1984”.

The letter of the Spaller family perfectly illustrates the fear present in those times, affecting both the public sphere and the everyday life of the individual. People, afraid they might be observed and harassed by the Securitate, in the constant climate of insecurity, chose to be silent, avoiding any form of public manifestation. It also says a lot that the senders of the letter did not give a Romanian address for direct correspondence, but that of the railway station in Biharkeresztes, a Hungarian settlement 6 km from the Hungarian-Romanian border, which is also a border crossing point.

The reasons behind emigration did not require much explanation back then. Beginning with January 1983 it became increasingly difficult to obtain a residence permit from the Hungarian authorities, as the application involved the presentation of a letter of invitation. This seemingly insignificant administrative obstacle – as revealed also in the above letter – could represent an enormous impediment for families who planned to emigrate, though emigration did not prove to be an impossible endeavour on the whole: in 1987 the Spaller family moved to Hungary where they managed to find jobs that suited their qualifications. At present they live in Budapest (Spaller and Spaller 2006).

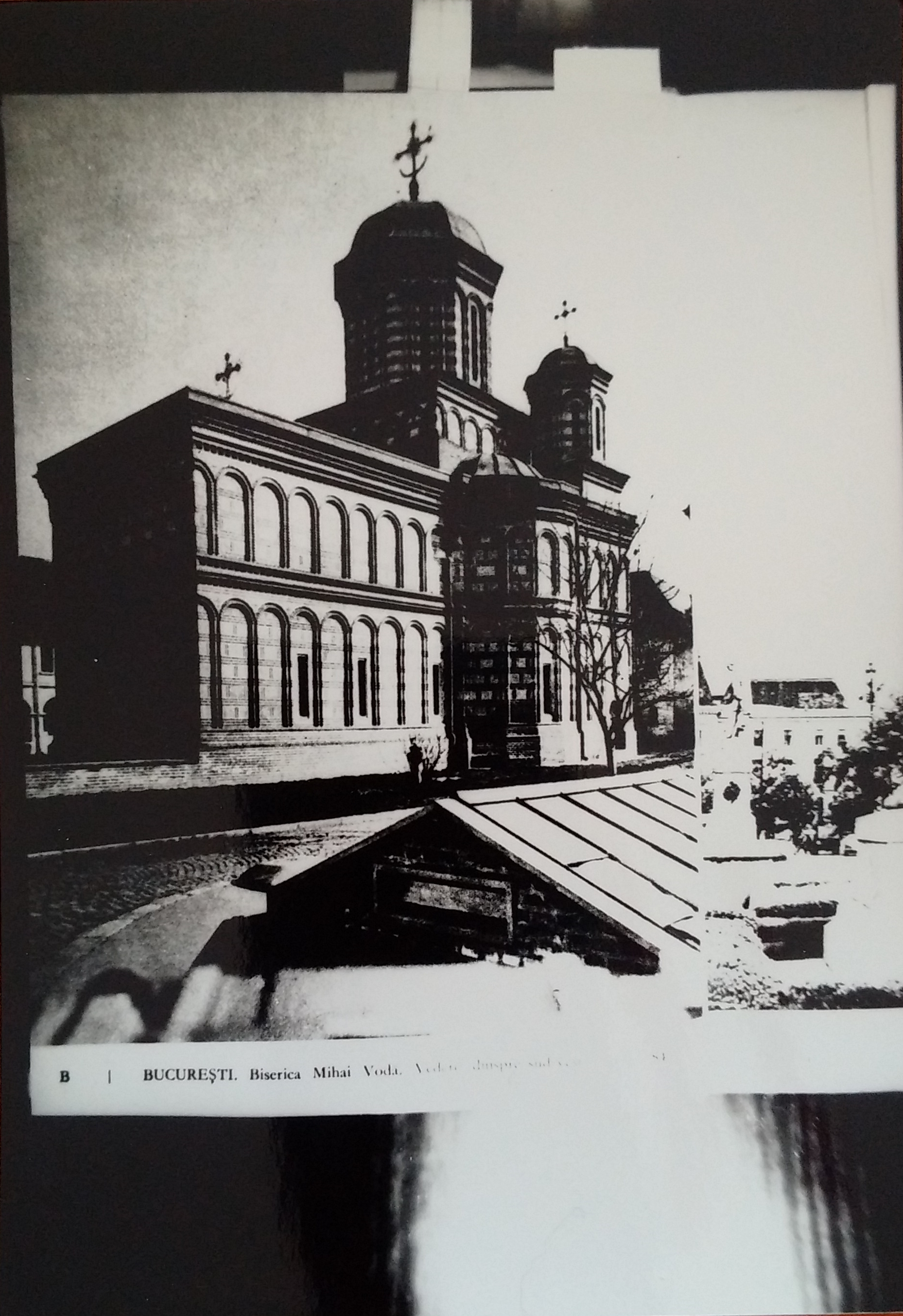

The church of the former Mihai Vodă Monastery is one of the oldest surviving buildings in Bucharest. The monastic complex of which it was part, nowadays partially destroyed, dated from 1594, and had served various purposes over the centuries, including princely residence, military hospital, and medical school. The most important of these was its transformation into the home of the State Archives after the founding and international recognition of the modern Romanian state in 1862. The Mihai Vodă monastery, an emblem of premodern Bucharest, was founded by one of the most important rulers in the pantheon of the national history of the Romanians, Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul), whence its name. As ruler of Wallachia in the period 1593–1601, he was the only leader of any of the premodern states existing within the present boundaries of Romania who managed to bring under his military control, “to unify,” for a very short time (1600–1601) a territory approximately corresponding to that of contemporary Romania. For this reason, Michael the Brave has been considered to be a key figure in national history, starting from the early nineteenth century and the first professional attempts to codify that history into a narrative frame. Paradoxically, communist historiography conferred on Michael the Brave an infinitely more important role in national history than he had ever been accorded by historians before the First World War or in the interwar period. Due to the teleological reading of national history that characterised the (re)interpretation of historical materialism in the time of the Ceauşescu regime, Michael the Brave came to be seen as prefiguring the so-called “Union of 1918.” This expression refers to the joining of the historical regions of Austria-Hungary with a majority Romanian population to the Old Kingdom of Romania, which did not in fact happen until after the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain (1919) and Trianon (1920). This historic moment became fundamental for the national identity of the Romanians following the (re)codification of national history under the direct guidance of the Party and the imposition of this version as representing the “single historical truth” through the intermediary of the documents adopted at the Eleventh Congress of the RCP in 1974. According to this interpretation, Michael the Brave was the first ruler who achieved the union of the Romanians and anticipated by his actions the culminating moment of national history, the “Union of 1918,” which was achieved by popular action from within, the “will of the masses” of Romanians, and not at the negotiating table. This image of Michael the Brave was intensely promoted under the Ceauşescu regime, not only through school textbooks or works of historiography, but much more efficiently through the intermediary of a cinematographic narration: the film Mihai Viteazul (1970), in which the protagonist is played by one of the best loved actors of the communist period, is to date the most viewed Romanian historical film, with over thirteen million viewers, and in third place in an overall ranking of films produced in Romania, with only 1.3 million viewers less than the film that takes first place.

In spite of the special importance of this historical figure in the redefinition and reproduction of national identity under the Ceauşescu regime, the monastery complex that he founded and that had constituted an emblem of pre-modern Bucharest became the victim of the most notorious of the demolitions ordered by the same regime. Due to the elevated position that it occupied in the urban landscape, its site was destined for the House of the People. Consequently, in 1985, the monastery ensemble was demolished, while the church and bell-tower were moved from their original position to make room for the communist architectural ensemble, whose pièce de résistance was to be the House of the People, today home to the Romanian Parliament. Initially scheduled to be demolished (and thus to share the fate of the twenty churches that were demolished between 1977 and 1989), the Mihai Vodă church was saved from destruction at the last minute. The compromise solution was to move it from the hill on which it had been established by Michael the Brave to a new position at the foot of the hill, where it would be hidden by the new apartment blocks that were to be built. As a result of the operation of moving the church down a slope, it was shifted a distance of 289 metres, descending by 6.2 metres. Initially sited on the Mihai Vodă Hill, at what was then Str. Arhivelor no. 2, it is now to be found at Str. Sapienţei no. 4. In the course of this process of radical reconfiguration of the centre of the city of Bucharest, another eight churches were moved in the same way as the Mihai Vodă church. These operations necessitated much inventiveness on the part of the engineers, and so may themselves be counted among the actions of cultural opposition, of finding a way not of directly disobeying the orders received but of moderating their consequences by proposing solutions that would be tolerated. In Alexandru Barnea’s private collection there are three photographs of this church, taken in 1985, a few months before it was moved. They stand as testimony to the policy of remodelling the past that was characteristic of the Ceauşescu regime, which made intense use of national history for the purposes of legitimation, but at the same destroyed all that did not fit the new secularised version of that history. By transforming all national history into a prehistory of the Communist Party, past rulers who had fought for “unity and independence” became precursors of the General Secretary of the Party, who – continuing their model – was trying to pursue a policy of distancing in relation to the Soviet Union. However all that did not fit the atheist vision of the communist regime was condemned to oblivion or even to destruction. Actions such as that of the collector Alexandru Barnea contributed decisively to the preservation of the pre-communist historical memory of the Romanians.

The many letters to be found in Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca’s collection are indisputable evidence of their commitment to using RFE’s broadcasts to protect Romanian dissidents from the abuses and acts of violence organised against them by the communist authorities. An illustrative example of this is the letter that Father Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa sent to Monica Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca in October 1984.

A former political prisoner, Calciu-Dumitreasa was imprisoned again in 1979 after delivering a series of seven sermons for young people the previous year. Through his sermons, Father Calciu-Dumitreasa hoped to strengthen the faith of young people whose Christian spiritual life was threatened by communist atheism and materialism (Petrescu 2013). The letter written by Father Calciu-Dumitreasa describes his situation and the situation of his family after his release from prison (August 1984) due to a huge campaign organised by the Romanian diaspora, and also makes known to the listeners of RFE’s Romanian desk his decision to emigrate.

At the beginning of his message, Calciu-Dumitreasa mentions that while imprisoned he refused any kind of collaboration with the regime. Furthermore, he continued to perform his duty as a priest despite the threats, terror, and beatings he was subjected to by the communist authorities. After his release, Calciu-Dumitreasa has been welcomed by his friends, acquaintances, and former students but to his very great disappointment the Romanian Orthodox Church has decided to strip him of the priesthood. Thus, in his letter he urges the Orthodox Church’s hierarchs to reconsider their position regarding his removal as he has proved to be a faithful defender of Christian values even in the most unfavourable circumstances. Moreover, the Securitate continues to watch each of his movements and its "unbated persistence in hate and malice" means that persecution against him and his family has continued.

In this context, Calciu-Dumitreasa mentions that despite his immense investment of love, faith, and suffering in "our country and Church," he has decided to emigrate due to the harassment his family continues to be subjected to by the Securitate. At the end of his letter, Calciu-Dumitreasa expresses his belief that those who have stood by him in difficult times in Romania will also surrender him with their love into his forced exile.

A volume of Jonynas’ writings was published in 1984, edited by one of his students, the famous Lithuanian historian Vytautas Merkys. It includes several previously unpublished works: Jonynas’ autobiography, and the article ‘Lithuanian historiography’. It also contains several letters from Jonynas from the interwar period to various foreign historians. Jonynas’ most important work ‘Vytautas’ Household’ was published for the first time in Soviet Lithuania. Practically all the documents were taken from the Jonynas collection.

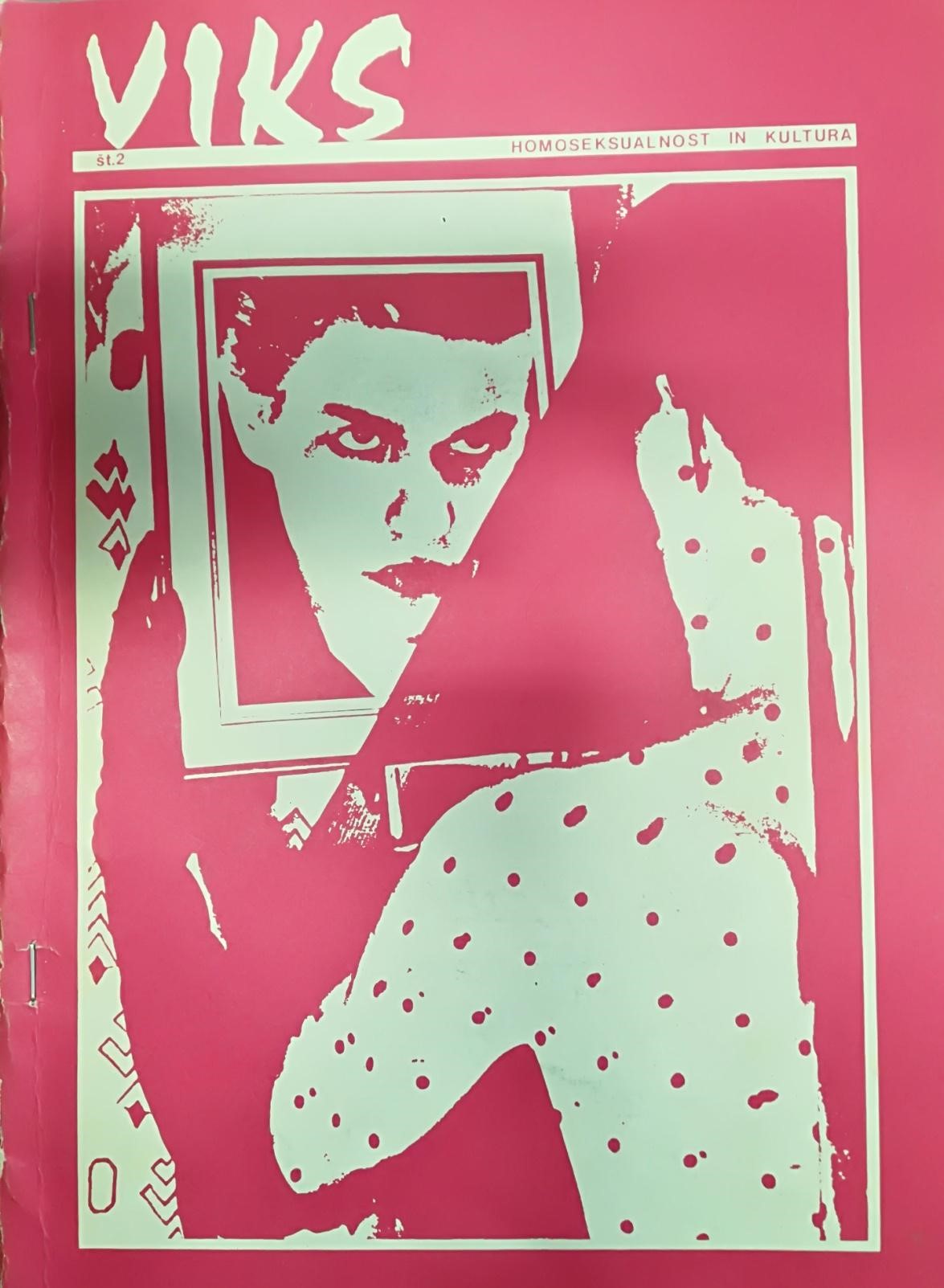

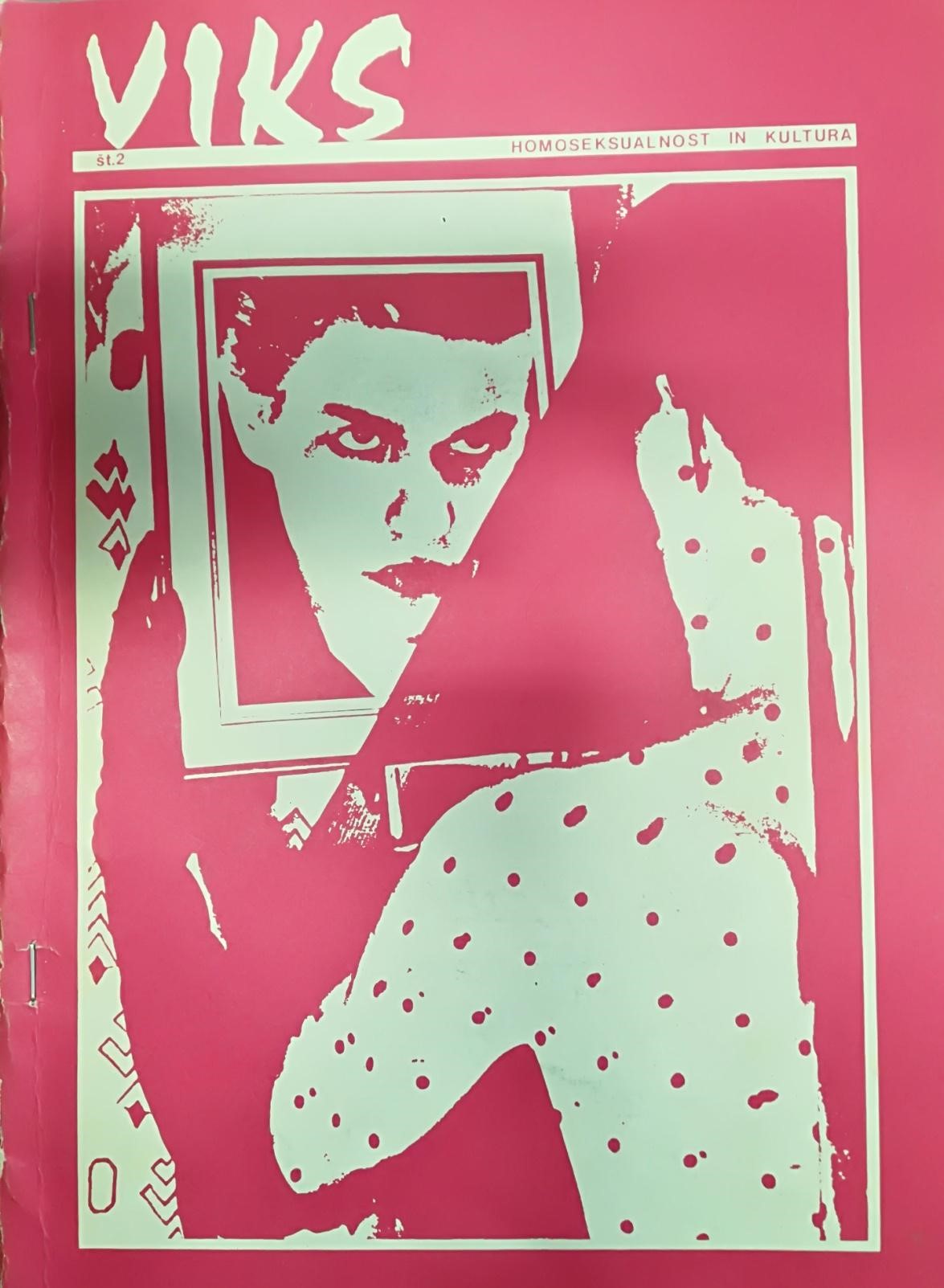

The second issue of the magazine Viks, entitled “Homosexuality and Culture,” came out on April 24, 1984, the opening day of the Magnus Film Festival, the first cultural manifestation dedicated to homosexuality in any socialist country. The magazine was edited by a group of gays and lesbians who gathered around the youth cultural center ŠKUC and organized the festival. This special edition of the magazine was printed in 600 copies and handed to audiences at the festival. It contains 42 pages, and approximately 20 illustrations with contemporary, easily recognizable European gay subcultural motifs. Over the three following decades, this issue of Viks gained a cult status in Slovenian and the post-Yugoslav LGBT community, and was exhibited at events dedicated to the history of homosexuality and the LGBT movement.

Alongside the festival’s program and a schedule of affiliated cultural and club events, in an effort to appeal to the younger generation of Ljubljana’s gays, lesbians and artists, Viks also carried several lengthy programmatic articles and interviews with emancipatory, educational and mobilizing overtones. Thus it aligned itself politically and theoretically with contemporary liberationist, leftist and counter-cultural movements in Slovenia and Western Europe. These texts promote an ideal of freely and openly lived (homo)sexuality. Non-normative sexual practices were viewed as strongly dissident in nature, but not so much against socialism as against patriarchal and traditional forms of sexual and family life.

The article “Pink Love under the Red Stars – Homosexuality under Real Socialism” (“Roza ljubezen pod rdečimi zvezdami – homoseksualizem pod realnim socializmom,” pp. 18-21) delivers a historical overview of the legal and social status of same-sex sexual and emotional relationships in socialist countries. The anonymous author is equally critical of the 20th century discrimination of homosexuality both in western liberal democracies and socialist countries. However, the Stalinist period in the USSR was seen as especially brutal and arduous insofar as it attributed negative political meanings to homosexuality, declaring homosexuals “traitors,” foreign “spies,” decadent bourgeoisie, and enemies of socialism. Soviet homosexuals, the article suggests, were not able to recover from this traumatic period, and were still unable to engage with emancipatory social movements and practices. At the same time, the example of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, known also as East Germany) is held as an example of both positive changes in communist stance on homosexuality, and a way in which, since the late 1970s, a dialogue could take place between the government and gay and lesbian groups.

Essay by Dorin Tudoran: Cold or Fear? About the Condition of Today’s Romanian Intellectual (in Romanian). 1984.

Essay by Dorin Tudoran: Cold or Fear? About the Condition of Today’s Romanian Intellectual (in Romanian). 1984.

By late 1983, Dorin Tudoran espoused increasingly radical ideas regarding the total failure and essentially flawed character of the communist system as a whole, which he saw as irredeemable and deeply corrupt. He had already made his views public in 1983 in a series of interviews with various Western press outlets, expressing his conviction that Ceaușescu’s Romania was an absolute dictatorship and seeing the communist system as the main cause of the Romanian people’s material and moral decay. In his essay written in early 1984, Tudoran proposed a complex analysis of the role and situation of intellectuals in communist Romania. Tudoran focused primarily on the causes of his colleagues’ subservience and total submission to the communist regime. He found the roots of this phenomenon in the persecution and déclassement of this stratum by the communist authorities after 1945, comparing them systematically to their peers in Central Europe. Among the factors which generated compliance, Tudoran highlighted the specificity of local political traditions; the terror of the first decade-and-a-half of communism, which led to a mass “moral capitulation” of the intellectuals; their complete reliance on the state for professional survival; and the skilful manipulation of their upward social mobility by the communist authorities. However, Tudoran argued that the compliance of the absolute majority of intellectuals in Romania was, above all, a direct consequence of Ceauşescu’s personal rule and of the Romanian communist system. The essay concluded that Romanian intellectuals had to reassert their responsibility toward the broader society by emulating and following the lead of their predecessors from the generation of 1848, who had succeeded in breaking with the political traditions of subservience to the state and had emancipated themselves by embracing synchronicity with the West. Rejecting the notion of “resistance through culture” as inefficient and outdated, Tudoran pleaded for an alliance with other social groups on the Polish model. In his opinion, this was the only way to limit the abuses of the communist system, as long as total change was still inconceivable. This work, viewed at the time as the most radical text written by a Romanian dissident since Paul Goma, still represents the best and most convincing analysis of the Romanian intellectuals’ plight under communism produced by an “insider.” Mihnea Berindei received a typewritten copy of the original text, in Romanian, which he then forwarded to the editorial board of the journal L’Alternative, recommending it for publication. It was in fact published in French later that year (in two parts, the first in L’Alternative, no. 29, September–October 1984, pp. 42-50, and the second in the following issue). In a special note to the editors, Mihnea Berindei stated: “the text turned out to be longer than required. If possible, I suggest its publication in two parts. If not, I would very much like to […] keep its structure, including the mottos. In other words, at least something from all the chapters should be kept, since the text has a certain structure and ‘strategy.’ Maybe the complete version would be interesting for another periodical, if it is not interesting for the journal that suggested its writing […]. It’s good that the text exists. It could also be printed under another, more attractive title!” This clearly shows Berindei’s personal role in steering the text toward publication and his position of intermediary between authors writing in Romania and the Western public sphere. Despite the apparent initial hesitations of the editorial board, Tudoran’s text had a rather significant impact on the exile community and also prepared the ground for the emergence of similar critiques in the following years. This masterpiece highlights Mihnea Berindei’s contribution to the “journey” of this fundamental text of Romanian dissent toward its target audience in the West.

The collection attracted the attention of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who visited the Keston College in 1984. Thatcher attended a reception in Church House, Westminster on April 25, 1984. The photo was taken by Derek Davis, most likely, a hired photographer. According to a Keston News Service report (No. 198, 3 May 1984), this reception was held in order to mark Rev. Michael Bourdeaux’s announcement as the recipient of the 1984 Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion. Sir Sigmund Sternberg and the Bishop of London hosted the event, as chair and co-chair of the newly formed “Friends of Keston College.” 200 distinguished guests were in attendance, among them Margaret Thatcher. She used the opportunity to praise the work of Keston College, noting that she often quoted information provided by Keston in meetings with other heads of government because of its reliability. Margaret Thatcher is associated with the systematic economic policies of neoliberalism that emerged under the Thatcher and Ronald Reagan governments. Neoliberalism confronted the planned economies of Socialist governments throughout the decades in which the Keston Institute was most active. These linkages between the Thatcher government and the Keston College/Institute highlight the intersection of religion and ideology with the politics of neoliberalism and human rights.

The Fine Art Archive consists of diverse documents connected to Czech and Slovak art of the twentieth and twenty first century. Catalogues, books, invitations, journals, photography, slides, cuts and other items have been gathered continuously since the mid-1980s.

Video published in December 2016 on the YouTube channel of VLS, 47’ 17”

The material was recorded in February 1984 at the University Stage, Budapest in the third productive period of the band, after the release of their first disc, during the concert entitled Aerobic. The performance was carefully arranged and included first-time performances of new songs, large scale stage design, and costumes painted for the occasion.

The most interesting aspect of the video – beyond its documentary value – lies in the history reflected of its mediality: according to the caption it was shot by a professional television team with three cameras, but it never was broadcasted, as several small characteristics of the material suggest, for example some parts of the image are missing and black blanks have been inserted, while the sound continues.

This YouTube video is most probably the digital version of the once half-cut material: it was abandoned at this stage, when it turned out that permission would not be granted to broadcast it. However, someone archived a copy on VHS. The quality of the image suggests that this tape was digitalized then and published on the internet 32 years after the event.

There are other interesting details: the method of editing songs separately breaks the original span of the concert, some parts were clearly left out; the cameramen sometimes stands in front of the performers; the totals were recorded through the reflecting window of the technician’s cabin, so the stage design is not very prominent.

However, the pillows fixed on the performer’s garb function perfectly. The stage presence of the artists is elemental and provocative. They restart the performance of several songs, and the program is intertwined with various spontaneous actions. Some of the songs sound provocative even today.

The record is a valuable document even in its fragmentary state. Although it shows only an episode from the history of the band, many interesting details of its spirit “come through” for the Hungarian-speaking audience (as there are no subtitles).

![Migrating Birds [Vándormadarak/Păsări călătoare], 1984, silkscreen print](/courage/file/n76628/6.+V%C3%A1ndormadarak.jpg)

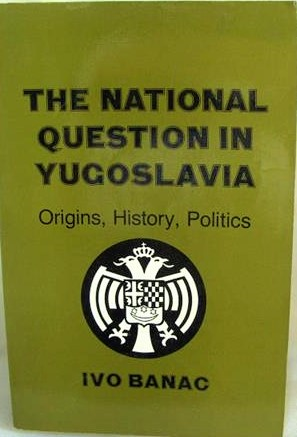

![Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics [Nacionalno pitanje u Jugoslaviji: porijeklo, povijest, politika], 1984. Knjiga](/courage/file/n2404/83297454.jpg)