The full title of this central document in the Marian Zulean collection is Întîlnire la nivel înalt: Moscova, 29 mai – 2 iunie 1988. Documente și materiale (Summit meeting: Moscow, 29 May – 2 June 1988: Documents and materials). The book documents in detail the content of the visit to the USSR made by US President Ronald Reagan in the early summer of 1988, at the invitation of Mikhail Gorbachev.

The volume consists of a series of transcriptions of the public moments of the meetings of the leaders of the two states, four speeches by each of them, press statements and addresses by Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan, transcriptions of question and answer sessions in front of the press, and the answers given by the Soviet leader in an extensive interview granted to the newspaper The Washington Post and the magazine Newsweek prior to the visit. The book also gives details of the ceremony of exchanging instruments of ratification with the reference to the coming into force of the treaty eliminating medium-and shorter-range missiles, and the text of the joint statement made at the Moscow summit. Not least among the interesting features of the book is a substantial photographic archive of the state visit.

In order to understand why such a book constituted an alternative source of information, it must be recalled that, in comparison, the reflection of this visit in the Romanian press was minimal. Marian Zulean remarks: “I remember that it was just mentioned briefly in short news items. Because in fact what was happening then between the USSR and the USA did not suit the leaders of the communist regime here at all. Once I read this book, to which I added what I heard on Radio Free Europe, I really understood what had happened during those days in the USSR.”

The book is preserved in good condition in the Marian Zulean collection. It has 128 pages and was published, directly translated into Romanian, by Novosti Press Agency in 1988. The book was purchased at the International Trade Fair for Consumer Goods (TIBCO), where the USSR had a very large stand.

Gediminas Ilgūnas was a well-known Lithuanian writer, journalist, ethnographer and traveller. In the 1950s, he was accused of anti-Soviet activity and imprisoned. On being released from prison, he and his close friends started to organise ethnographic expeditions, collecting material about important personalities in Lithuanian national history. The collection holds various manuscripts, including documents relating to his activities in the Sąjūdis movement and his political activities as a member of the Supreme Council, short memories about the Stalinist period, and material collected for a biography of Vincas Pietaris. The collection shows the actions of a Soviet-period cultural activist who tried to collect and preserve Lithuania's past culture.

In 1988, Berlin became the cultural capital of Europe. For the occasion, the German fashion designer Claudia Skoda was asked to create a fashion show by inviting artist from different corners of Europe. Skoda invited Király, who was the only representative of the Eastern Bloc. His collection was strongly inspired by Oskar Schlemmer’s costumes at the Triadic ballet in that he created his dresses using only circles, triangles, and squares from the perspective of design and only red and black colours separately from the perspective of colour. In the end, he created 40 dresses, of which three have survived as part of his bequest.

The documentary entitled, “Parcel 301” (1988) brought Black Box fame. The film presents the inauguration of a memorial designed by László Rajk in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, on the 16th of June 1988, and the commemoration ceremony of the 1956 revolution and Imre Nagy that turned into an anti-dictatorship demonstration in Budapest on that same day. It is based on reports and interviews with 1956 revolutionaries, relatives of those executed for their involvement in the revolution, as well as political opposition figures. On the 16th of June 1988, the 30th anniversary of the execution of Imre Nagy and other martyrs of the revolution, there was an unveiling of a monument for the victims of the 1956 Hungarian revolution in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. That same day, in Budapest, a commemoration of the revolution began at the unmarked graves of Parcel no. 301 in the Rákoskeresztúr Cemetery. The commemoration turned into an anti-dictatorship demonstration that continued at the Batthyány eternal flame and Heroes’ Square. The victims’ relatives and ’56 revolutionaries recalled 1956 and what this day meant to them.

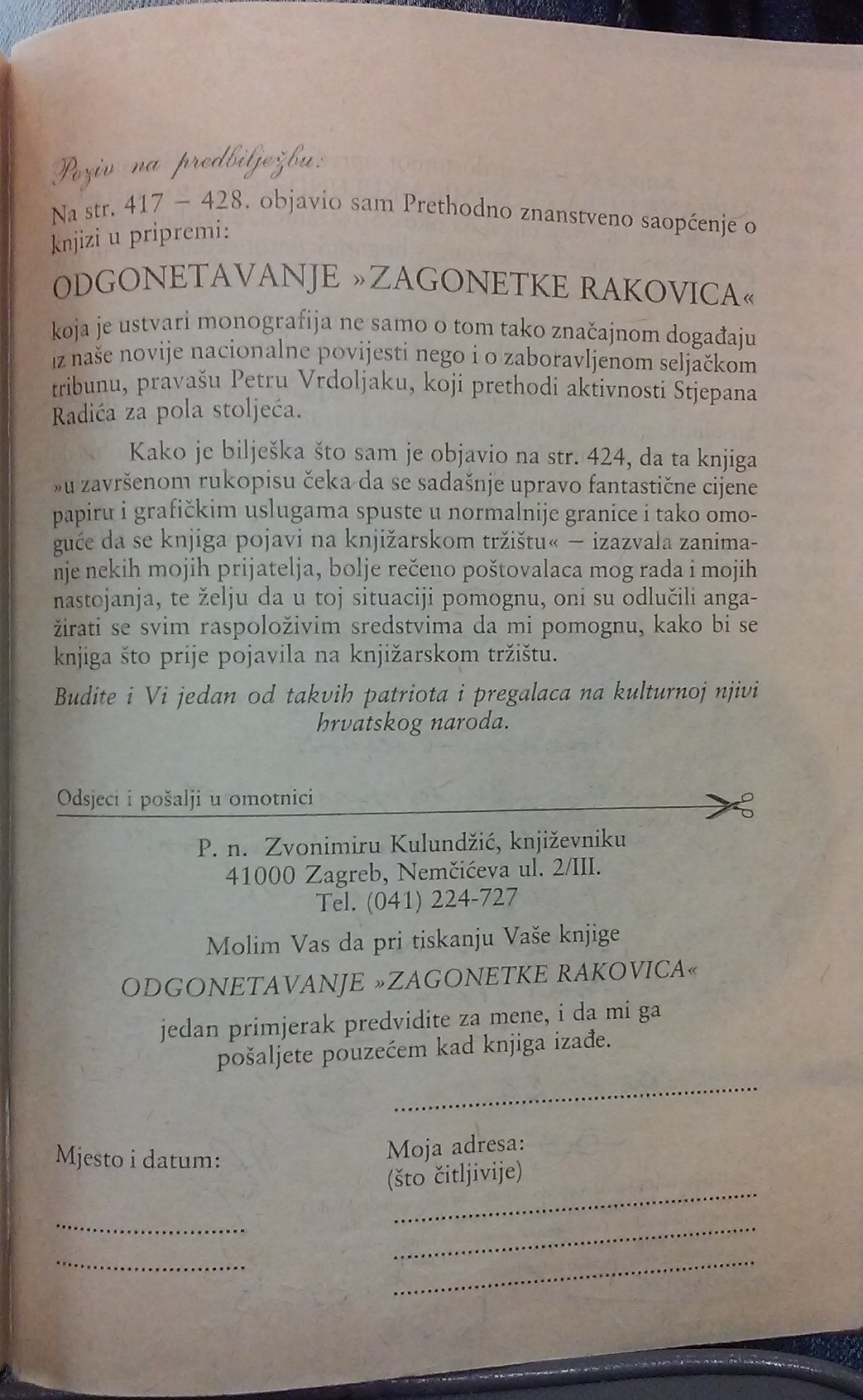

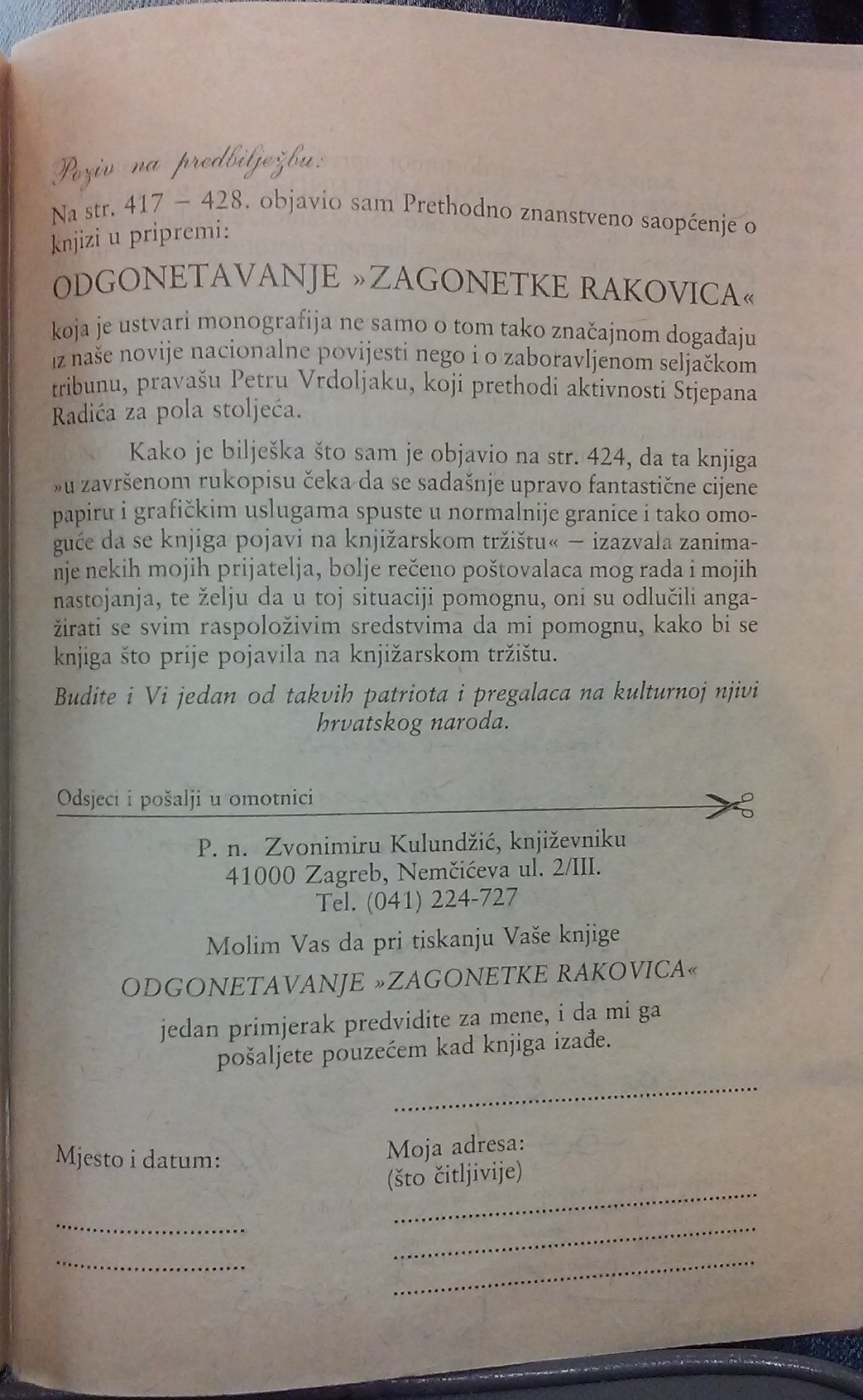

Publishers did not want to release some of Zvonimir Kulundžić's polemic books. On the other hand, Kulundžić himself was not ready to make compromises which some publishers were demanding. Therefore, Kulundžić published some of his most important books in his edition, without any institutional support. Nevertheless, some of his books were printed in a large number and were even sold out, such as the book Tragedija hrvatske historiografije (Tragedy of Croatian Historiography) (Zagreb, samizdat, 1970). Kulundžić gained readers quickly because of his controversial attitudes, subjects he dealt with and the thesis he offered, but also because he communicated directly with readers. In his books, he invited readers to buy his books directly from him. Most of Kulundžić's readers were subscribers of his self-published editions. This featured item - "Call for Pre-Order" - is the last page of the 2nd edition of the book Tajne i kompleksi Miroslava Krleže: koje su ključ za razumijevanje pretežnog dijela njegova opusa (Secrets and Complexes of Miroslav Krleža: which are the key to understanding the overwhelming part of his opus) (Ljubljana: Emonica, 1988). In this book author announces the release of his new book Odgonetavanje zagonetke Rakovica (Unriddle of Rakovica's Riddle) (Zagreb: Multigraf, 1994) and invites readers to ask for a copy of the book, saying "Let you become patriots and preachers on the cultural site of the Croatian people". He instructs the reader to cut off a part of the book (order form) write his home address with the text: "Please ensure a copy of your book Unriddle of Rakovica's Riddle, and send it to me when the book comes out."

The eight-page text written by the Czechoslovak historian and dissident Milan Hübl introduces its readers to the issue of convicts and their language. At the beginning are some brief but very interesting statistics comparing the sentences and records of criminal offences (regardless of length of sentence) in the years 1925, 1928, 1978, 1979 and 1980. Hübl goes on to write about prison structures and prisoners. The main focus of the text is prisoners’ slang. Hübl was familiar with this topic because he had also been imprisoned for several years. His own correspondence, written during his imprisonment between 1972 and 1976, is among the sources for this chapter, which focuses on the prison slang in the Brno region, the so-called “plotňáčina”. The text ends with following sentences: “While browsing through my letters, I realised that they would be a valuable source when I started writing my memoirs. A lot of information has been preserved that would have been difficult to recall without them. At least something positive came from being in jail.”

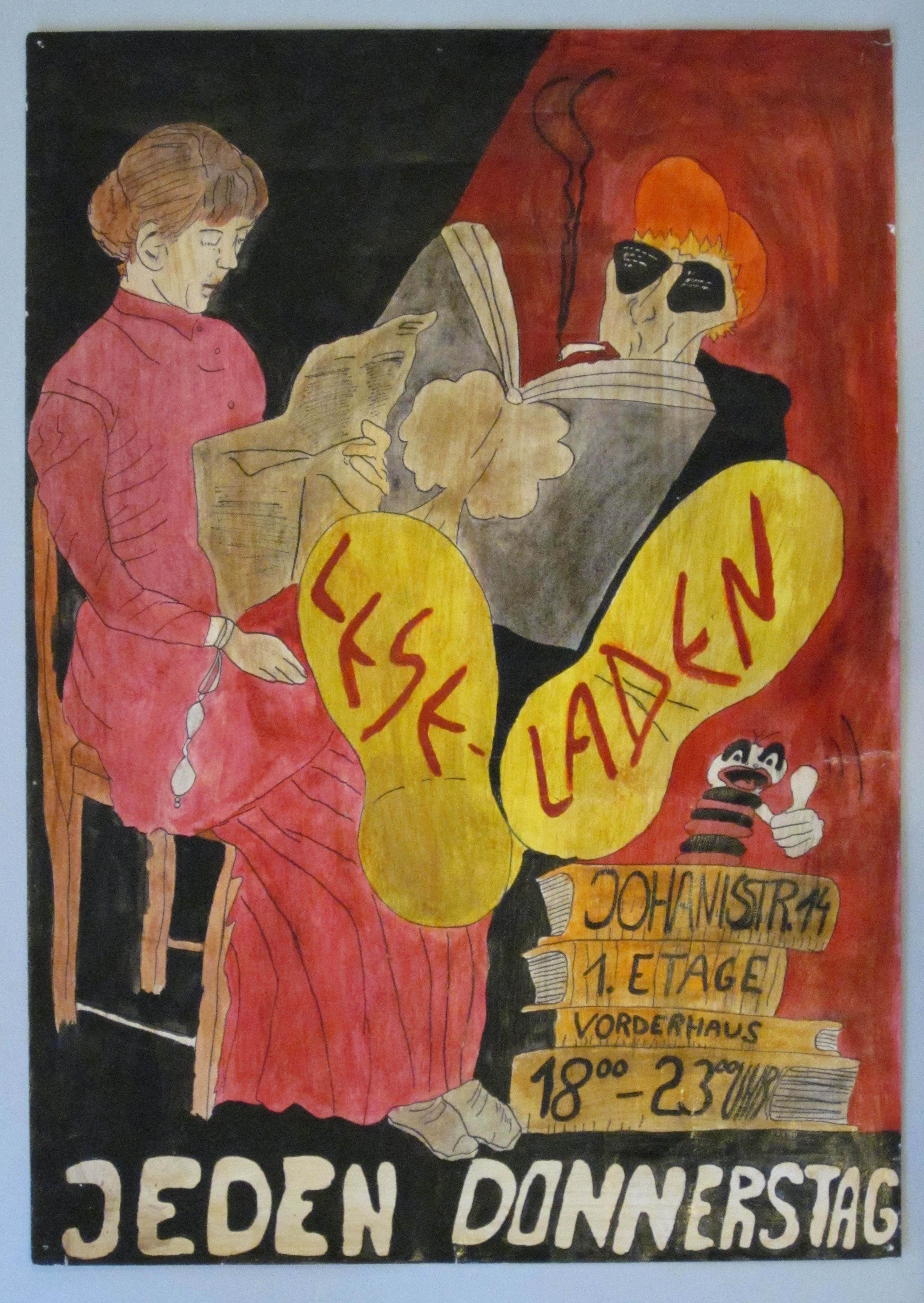

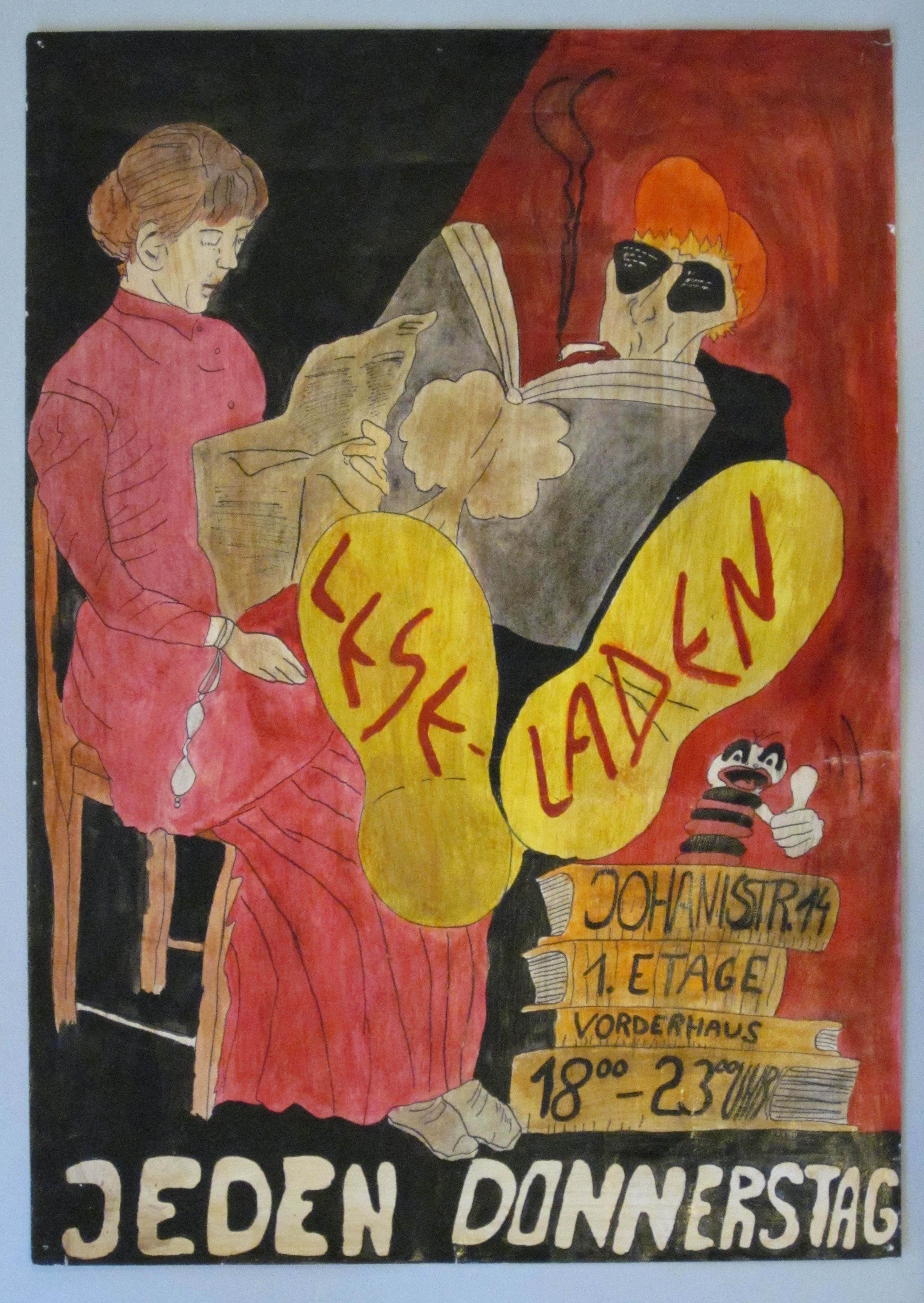

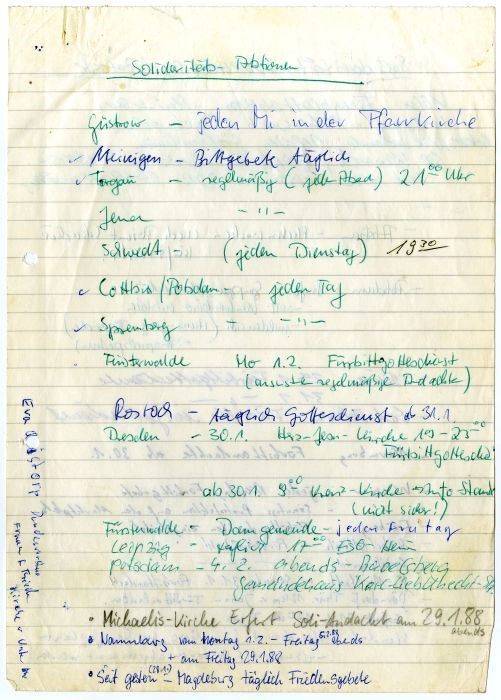

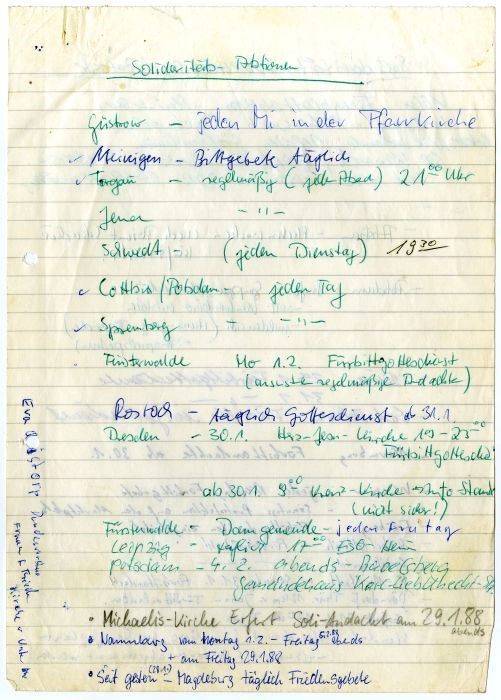

On 17 January 1988, around the periphery of the traditional march commemorating Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, which had long since become a mere ritual, a group of protestors unfurled a banner with the famous words of Luxemburg “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who think differently.” They, along with many other protestors were arrested at the end of the demonstration, with some being forcibly extradited from the GDR against their will. This measure and its consequences are a key element in the prehistory of the “Wende” of 1989. Owing to the lack of publicity, little was known about the events or the protests and solidarity demonstrations which followed it. As a result, the so-called “Telephone Contact group” was created in Berlin. They distributed their number across the GDR via the structures of the church. Similar to an autonomous investigation committee, the group gathered information on the reactions (and mood) in the country. The notes which have been preserved here pinpoint where and when demonstrations and other acts of solidarity with the “Luxemburg-Liebknecht demonstrators” could be found. Marianne Birthler, who would later go on to become the Federal Commissioner for the Documents of the State Security Service of the former GDR, also belonged to the “Telephone Contact Group” and passed this on to the Robert-Havemann Society.

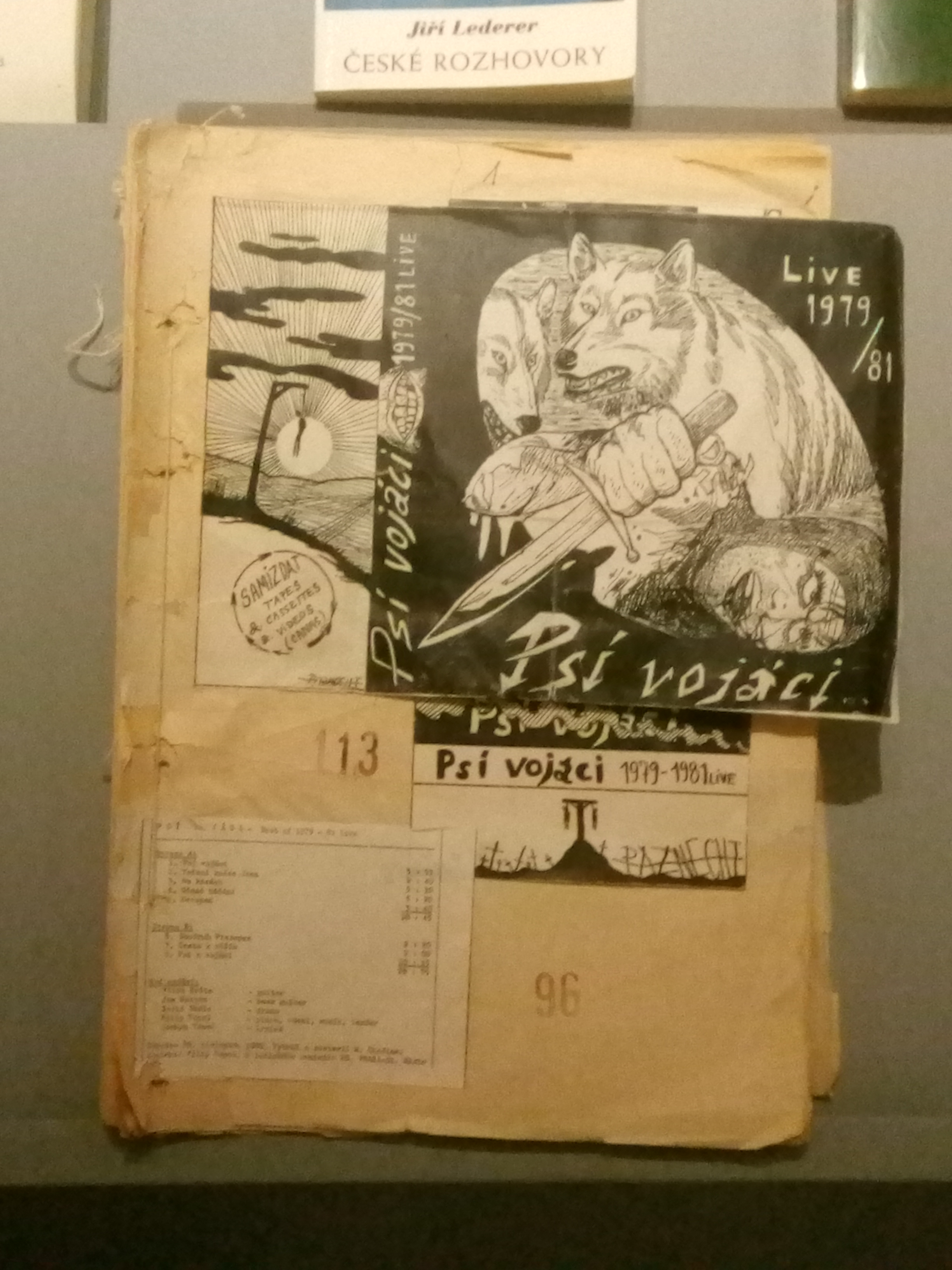

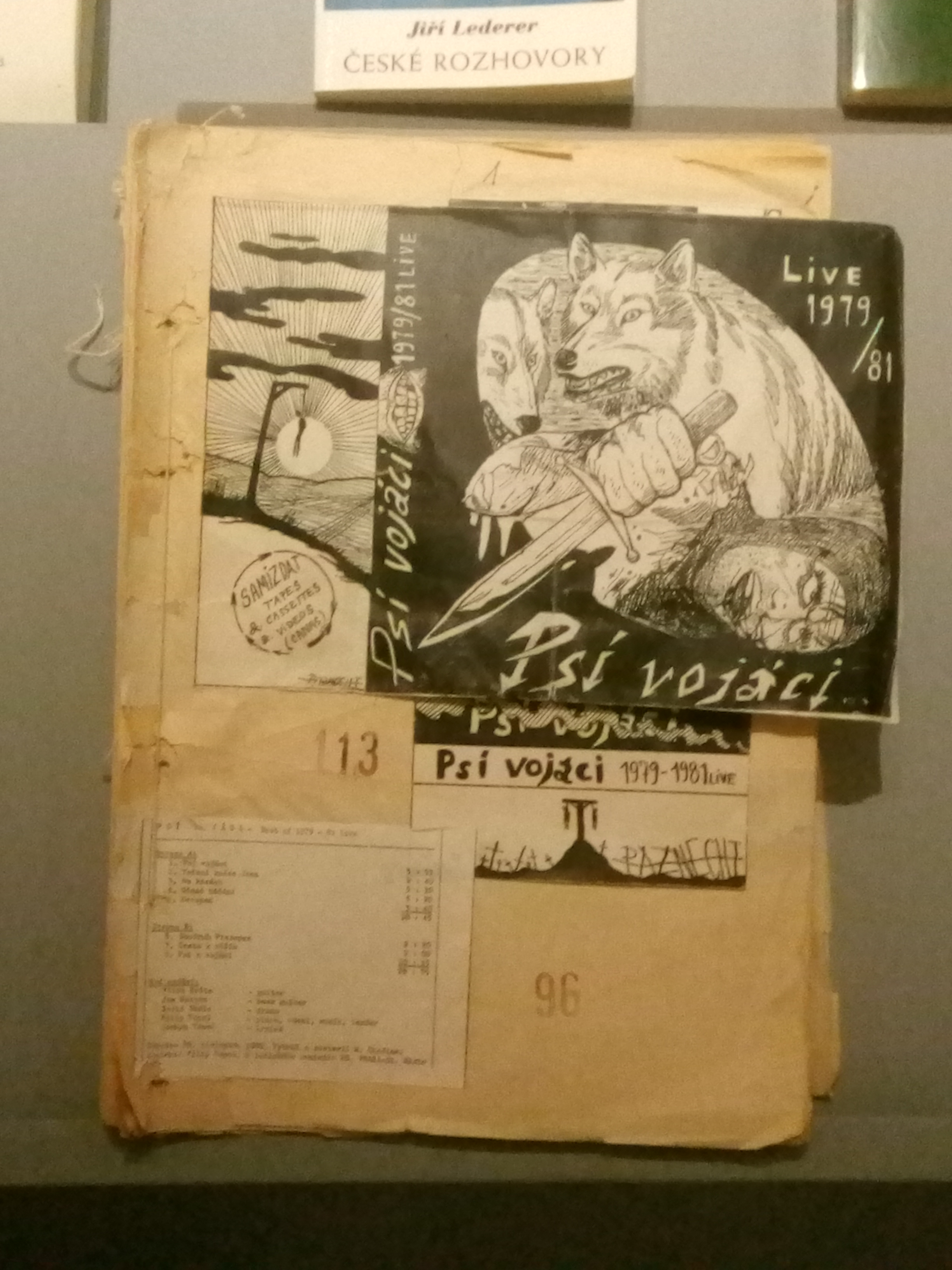

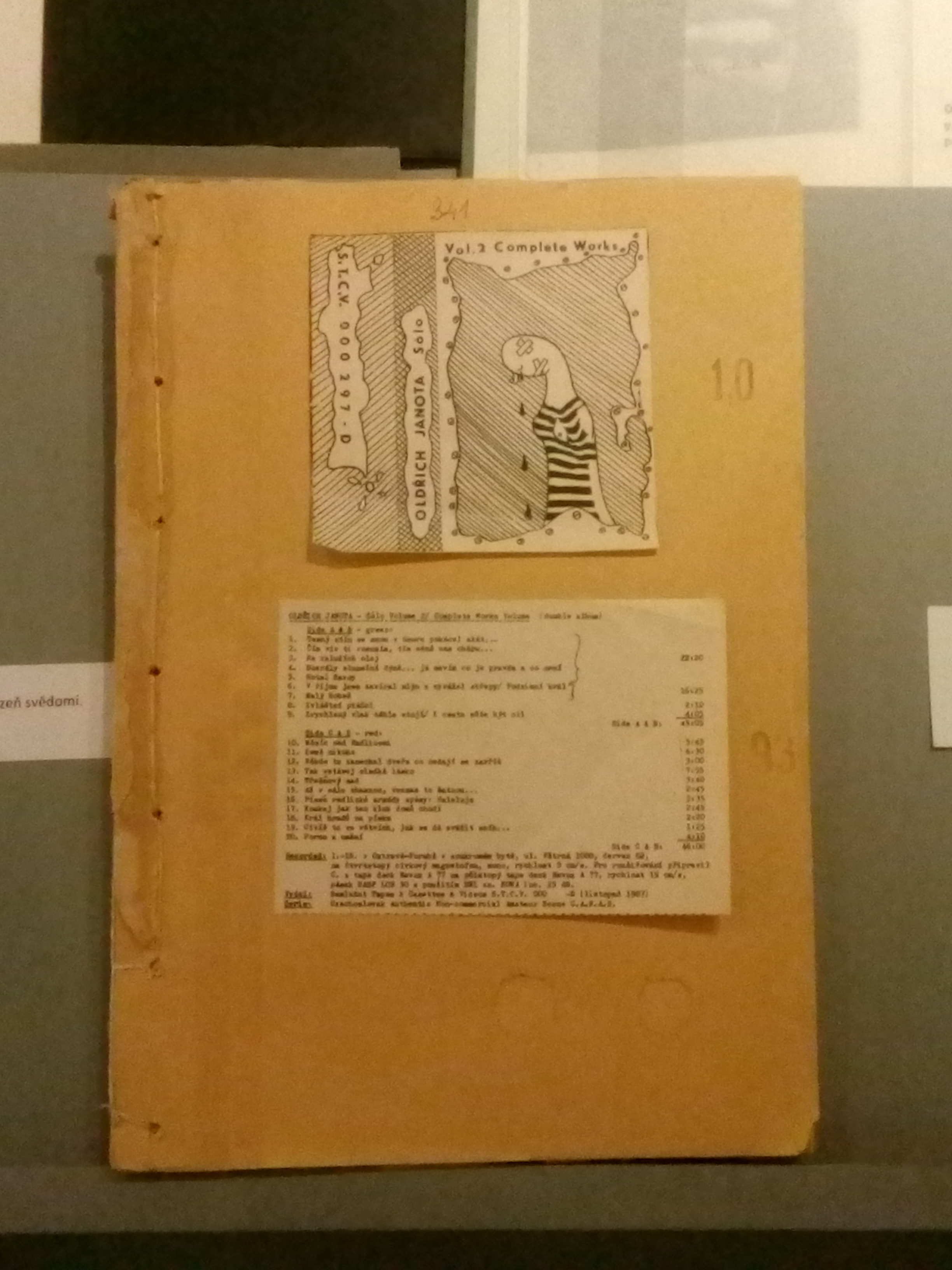

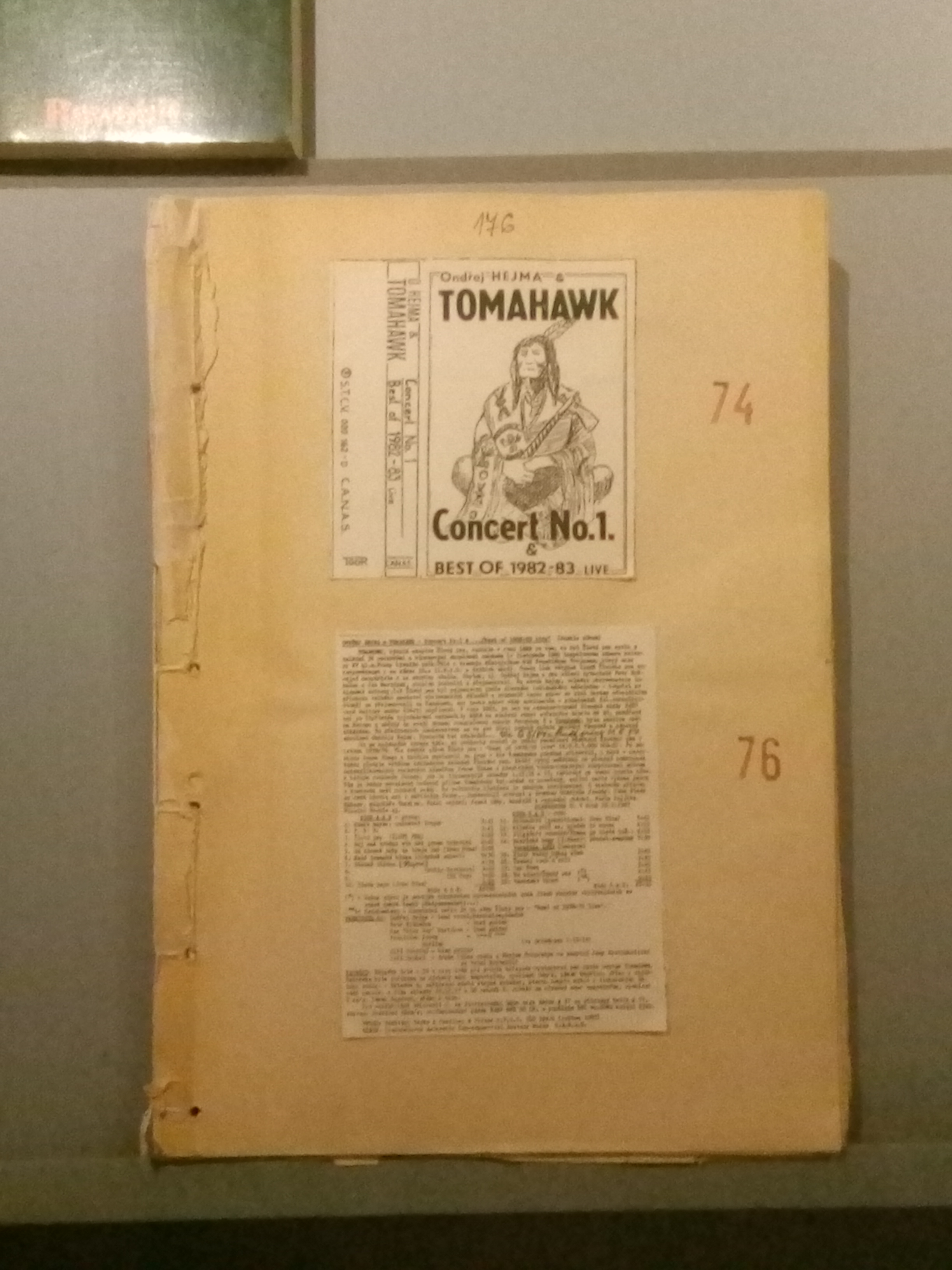

The Audiovisual Section of Libri Prohibiti contains three “books” – sheaves of paper – made from covers of cassettes of unofficial music groups from 1980s Czechoslovakia. The sheaves were made by the State Security (StB) from items confiscated during the prosecution of Petr Cibulka, a political activist and collector. During the 1980s, Cibulka recorded both concerts and amateur studio recordings, which he then produced and distributed in his samizdat record label S.T.C.V. (Samizdat Tapes & Cassettes & Video). Cibulka’s collection – hundreds of recordings and covers – was probably the biggest private collection before 1989. Cibulka was, because of these activities, sued in 1988 and imprisoned for “unjust enrichment” and his collection was confiscated by StB. The sheaves should have been evidence of his activities. A lot of original cassette covers were made from photo paper. The “books” therefore testify to the originality of producers of samizdat recordings. The item was presented on the travelling exhibition COURAGE “Risk Factors: Collections of Cultural Opposition” between 21 September and 28 October 2018 in the National Monument in Vítkov, Prague.

The Marian Zulean collection contains a brochure by Mikhail Gorbachev that summarises the main lines of the vision of the new Soviet leadership regarding the policies of glasnost and perestroika. The title of this little book in Romanian is Restructurări revoluționare: O ideologie a înnoirilor (the English edition is entitled The ideology of renewal for revolutionary restructuring) and it was published in 1988 by the Novosti Press Agency. Its presence on the market of publications in Romania was mediated by the International Trade Fair for Consumer Goods (TIBCO), an event held annually in Romania during the communist period, at which the USSR had a prominent stand.

The document, which is preserved in good condition in the Marian Zulean collection, gives a Romanian translation of the speech delivered by the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at its plenary meeting on 18 February 1988. Of this event, Mikhail Gorbachev says: “Our plenary is taking place in a period of responsibility for restructuring. The democratisation of social life and radical economic reform demand from the party a clear perspective on actions” (Gorbaciov 1988, 3).

A first observation that can easily be made after reading this document concerns the abundance of references to the key concepts of Gorbachev’s policy, perestroika and glasnost. They are mentioned dozens of times in the sixty-two pages of the document, but not in the original Russian forms in which they enjoyed an international career, including in English, but translated into Romanian as “restructurare/reconstrucţie” and “transparenţă”. On the basis of these key concepts of Gorbachevism, the brochure makes many suggestions for actions that obviously undermined the strictest rules of communism. Here, for example, is a single quotation in which the idea of egalitarianism is undermined, from the podium of the greatest communist party in the world and from the mouth of its supreme leader: “In general, comrades, we must deal thoroughly with the problem of eradicating egalitarian approaches. This one of the most important social-economic and ideological problems. Egalitarianism, in its essence, exercises a destructive influence not only over the economy, but also over morality over people’s whole way of thinking and acting. It diminishes the prestige of conscientious and creative work, weakens discipline, stifles interest in increasing qualification and the spirit of emulation, of competition in work” (Gorbaciov 1988, 34).

In Marian Zulean’s assessment: “This brochure authored by Mikhail Gorbachev was a precious book at the time.” It’s value came from the discrepancy between the ideas promoted by means of it and those that characterised official discourses in Romania. “While the URSS was becoming more open and had a discourse that was less and less in contradiction to the ideas of the West, in Romania, it was exactly the opposite. They were becoming more open; we were becoming more closed. You could try to read from this booklet in public, but it was safer to think well a few times before doing so. There were a lot of risky pages in it.” In other words, in the conditions of cultural isolation in which Romania found itself at the end of the 1980s, a brochure like this was one of the few sources of exposure to alternative ideas and a precious help to those who wanted to emancipate themselves from the dogmatic constraints in Romania and to be able to think critically and freely.

Vytautas Skuodis (1929-2016) was a Lithuanian scientist, Soviet dissident and former political prisoner. From 1979, he was a member of the dissident organisation the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. In 1978, he initiated and edited the journal Perspektyvos (Perspectives), the most recognised underground publication among the Lithuanian intelligentsia. The Vytautas Skuodis collection holds various manuscripts of Skuodis’ monograhs, a PhD dissertation, articles, lectures, letters, reviews of diploma works by students, notes, memoirs and diaries. These documents are relevant to the topic of cultural opposition, because they reveal personally the involvement of Skuodis and other people in anti-Soviet activities.

The ‘Fuck 89’ collection is an archive of Warsaw anarchistic movement from the last years of state socialism and the beginning of capitalism. It documents activities of groups such as A-Cykliści (A-Cyclists), Alternative Society Movement, Wolność i Pokój (Freedom and Peace), Intercity Anarchist Federation, and others.

"Monty Cantsin is a multiple personality pseudoname, an open-pop-star project. Anybody can be Monty Cantsin.

Neoism has no definition, and it doesn't mean anything specific. You can become a neoist by doing everything in the name of Neoism and by calling yourself Monty Cantsin."

Dominik Tatarka was a famous Slovak writer that became a “banned author” after 1968. He criticized Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and he was the first Slovak signatory to Charter 77. Thus, some of his books were published as samizdat or in exile. Tatarka’s book “Navrávačky” was first published in the samizdat journal “Fragment K” in 1986 (the first part) and 1987 (the second part). In 1987, this book was published in the samizdat edition “Petlice”. Then, this text was issued in exile – “Navrávačky” was published in 1988 in Western Germany in Cologne within the exile edition “Index”. These samizdat and exile editions of “Navrávačky” were prepared by Martin Šimečka and Ján Langoš. “Navrávačky” are book of Tatarka’s memories, opinions, and messages about culture, society or his life. This book is based on Eva Štolbová’s interviews with Tatarka that were recorded on twenty tapes during years 1985 and 1986. However, the text of these samizdat and exile editions was modified and rewritten as Tatarka’s monologue (in prose), without Štolbová’s questions. Later, in 2000 and 2013, “Navrávačky” was published in an original and complete version, as a transcription of interviews from tapes without any modification.

At the launch of the underground magazine the first challenge the editors were faced with was the political embedding of the product. This was done in the editors’ note (“Beköszöntő”) of the 29-page first edition and in Balázs Sándor’s programmatic article (“A Ceaușescu-korszak után” – After the Ceaușescu era). The title of the magazine was borrowed from a post-Trianon publication of the Hungarian community in Transylvania, which had found itself turned into a minority. Although the social-political circumstances in the interwar period differed in several aspects from the situation of the 1980s in Romania, the similarity between the existential situation of the minority in the two periods was considered more important. The editors revealed an analogy between the former outstanding personalities of Transylvanism and their own strivings. At the same time, they saw a resemblance between the post-Trianon mood and the spirit of hopelessness which existed during the decades of communism, characterised by: “despair, hesitation, idleness, the lack of creative energy, paralysis, turning away from politics, shattered self-confidence, escape fever, etc.” However, beside the words with negative meaning, the editors made use of the positive message of the 1921 Kiáltó Szó, which they tried to incorporate in their political statement with expressions like: “urge to act,” “restoring shattered self-confidence,” “work for the survival of the community instead of lamentation,” “developing the sense of reality instead of dreaming.”

They believed that the Romanian state had to take into consideration an ethno-cultural community as numerous as the Hungarian minority. They considered it important to establish a party on the basis of nationality which would represent the interests of the ethnic minority but in the context of Party-state dictatorship this called for a fundamental prerequisite, namely, the abolition of the one-party system. Organising a party was thus not an immediate option; they merely wanted to imprint the idea of this necessity in public awareness. By raising the issue, they implicitly adopted a position in favour of a multi-party system and of “real (not mocked as socialist) democracy.” As they could not imagine the implementation of multi-party democracy in the near future, they separated tactical (immediate) goals from strategic (long-term) tasks. The strategic task, that is, the abolition of the totalitarian regime, could not be formulated as an objective considering that this depended on the coordinated action of the entire Romanian society; therefore they only alluded to it. Thus, the emphasis was laid on the tactical goals, on preserving the Hungarian ethno-cultural community in Romania “until the time comes to participate in change.”

Continuing the tradition of their predecessors, the editors believed in the direct proportionality between fairness and loyalty, according to which the state could expect only as much loyalty as was justified by the degree of fairness it displayed towards minorities. The editors did not act against the Romanian state, but strove to put an end to discrimination against the Hungarian minority and to achieve a real democracy where loyalty too could be fully expressed. They were not against the state, and, as they expressed in their programme objective, they did not want a revision of borders. The distributed writings and the attached interpretations illustrated that the target of their criticism was the Party dictatorship. In particular, they tried to dispel the misconception according to which the dictatorial couple was responsible for everything, as they were fully aware that even if the dictators were eliminated, the Party apparatus would remain, and so their replacement would not solve the problem.

The editors of this samizdat doubted the idea shared by many according to which the Hungarian minority in Romania would play the role of a bridge not only between Hungarians and Romanians, but implicitly, between Hungary and Romania. Therefore they formulated and applied their threefold slogan towards Romanians: form an alliance with the Romanian democratic forces, win over the misled Romanians, consistently fight against Romanian nationalism. They tried to nourish the sense of interdependence and made efforts using their modest means to promote the necessity of a joint Romanian–Hungarian action. When presenting their political creed the editors strove to show their sympathy with those who held similar or identical views; in this regard they sympathised with the authors of the previous samizdat – Ellenpontok (Counterpoints) – as well as with Károly Király who at that time was a legendary figure of political resistance.

In his optimistic piece entitled “A Ceaușescu-korszak után” (After the Ceaușescu Era) Balázs dedicates seven paragraphs to the discussion of the tasks, the tactics, and the clarification of the legal status of the minority in the period up to the establishment of plural democracy, “preserving ourselves for the future.” The key point of his conception is, among general democratic rights, the need for collective rights to be granted to the minority, and further on, the securing of various forms of autonomy for the national minority. In the paragraph dealing with politics he speaks up for the political representation of the minority, where the nationality-based party separately representing itself at the elections is a political grouping guided primarily by the minority point of view in a multi-party social system. Nevertheless, this party will voice its opinion not only about minority problems, but also with reference to general issues concerning the country. In economic policy he argues in favour of unimpeded private initiative, stating that minority initiatives, both individual and group-level – cooperatives, economic associations, private companies – must be made possible in places densely populated by Hungarians. As far as culture is concerned, he stresses the importance of a licence accorded to the community (at the time referred to as either nationality, national minority or Romanians of Hungarian origin) that will enable them to manage their own affairs, especially cultural issues, independently. This requires a proper institutional framework which means, in fact, cultural autonomy. The article discussing the tasks underlines that this autonomy – be it cultural or not – is not meant to serve disconnection and that the editors of the samizdat have no intention of using the potential autonomy for purposes of boundary revision.

The part dedicated to education discusses the prospective restoration of the Hungarian-language Bolyai University and of the old Hungarian school network as well as the possibility of carrying out scholarly work in the Hungarian language in own institutions. When touching upon the free use of the mother tongue as one of the most essential minority rights, Balázs asks the state for guarantees as regards the validation of this abstractly stipulated and theoretically acknowledged “constitutional right.” He thinks that this right should be concretely included in several laws, as well as in the constitution. Thus there should be laws to regulate the introduction of multilingual signs in places also inhabited by minorities, the use of the Hungarian language in court and during official procedures, etc. He also argues in favour of the re-launch of Hungarian television programmes and local radio broadcasts. All this could have been considered as an act of revendication since the Romanian nationalist policy strove to restrict the use of the minority mother tongue most of all. The tactical measures include an inventory of clerical complaints, including problems linked to clergy training and difficulties concerning the bringing out of church publications. This last paragraph of the article asks for an elimination of discrimination between the domineering Orthodox religion of the Romanians and the so-called “Hungarian” religions the minority adheres to. The articles discussing the political statement as well as the “draft political programme,” besides representing a proof of civil courage, belong to one of the most significant historical documents of the years preceding the change of regime in 1989.