Gyöngy és homok: Ideológiai értékjelképek a magyar irodalomban (Pearls and Sand: Ideological Value-Symbols in Hungarian Literature) is a literary historical-aesthetic study of the so-called "pearl-mussel motif” so popular in the Transylvanian lyrical creation of the 1920s and the 1930s, also present in the subsequent periods. Beyond this, it is also an analysis of the underlying ideology behind the poetic image, that is, of Transylvanism. This work did not originally express an explicit ideological challenge to the communist regime, but its fate of being confiscated by the secret police transformed it into a significant part of Gyimesi’s intellectual legacy directly linked to her dissident activity, as József Imre Balázs points out. At the same time, in its cultural meaning, Pearls and Sand was a genuine “oppositional” work, whose critical understanding of Transylvanism brought a refreshing critique of the dominant tradition of the Hungarian minority culture before 1990. The reframing of the concept of Transylvanism after the First World War focused on the idea of a federal Transylvania within Romania consisting of ethnically diverse independent cantons organised after the Swiss model. Even if the enormous demographic changes in Transylvania brought about by the Romanian political leadership during the last decades of communism would have thwarted all real chances of seeing this implemented, Transylvanism remained an influential ideology among the members of the Hungarian community and a fertile ground for literary and artistic creation.

Early Transylvanism of the Hungarian community was a response to the traumatic territorial changes that culminated with the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty and created a de facto, formerly inexistent minority community, which was separated from its “mother country.” Under these circumstances there was a need to define the self-awareness of the Hungarian minority and to strengthen its national identity. This “strategy” of survival was much needed as the political-moral collapse of the Hungarian ruling elites following the military defeat in 1918 drove many people to suicide, alcoholism, or emigration. By 1924 as many as 200,000 people emigrated from Transylvania to Hungary. Transylvanism was a spiritual-moral defence, a positive response to the negative consequences of the Trianon Treaty which facilitated the moral acceptance of the situation the Hungarians in Transylvania found themselves confronted with. Its primary ideological function was to turn necessity into virtue: presenting disadvantage as an advantage, regarding the self-reliance of the minority as a beautiful possibility for independence, as a chance for creating specific values. This is how Transylvanism compensated for the sense of loss generated by the new situation. In the light of survival this ideology played a positive part, as in the so-called heroic era it helped Hungarians in Romania to recover from the post-Trianon trauma. It must be mentioned that this ideology was shared by a rather small group of people whose members undertook the mission, the sacrifice, mainly out of Christian faith; however, it is evident that this personal belief could not be turned into the ideology of one and a half million people.

The criticism of Transylvanism started already in the second half of the 1930s with the so called “populist” writers. They reached the conclusion that Transylvanism was not the sober conscientisation of the minority situation and of fundamental Hungarian interests, but a mere “faith and aspiration,” or wishful thinking, which created a false image of reality. The historical facts used as arguments represented, according to these critics, half-truths that were over generalised by writer-ideologists to cover up other mainly negative historical facts. This illusory image of reality proved to be necessary in the further stages of minority life as well and it fulfilled a similar role. After the Second World War both proletarian internationalism and the illusion of the “Danube basin” fraternity aimed at mitigating the conflicts of interest between winners and losers, between majority and minority. After many writers and cultural activists officially rejected the “dual commitment” in 1968, Transylvanian regionalism regained its former prestige, also strengthened by the newly established minority institutions. The manipulations of the Ceaușescu regime and the cooperative attitude displayed by certain Transylvanian Hungarian representatives towards a more liberal version of Romanian communism seemed to facilitate the validation of this illusory regional self-esteem. Accordingly, Transylvanian ideology revived again in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, when the need for redefining the collective identity of the Hungarian minority re-emerged, while its existence as minority was still unsolved. This appeared primarily in the conscious revival of tradition, as in Ernő Gáll’s historical works and in his ideology focused on the “dignity of the individual.” The publications of György Beke and the poetry of the second Forrás-generation poets also maintained the illusion of positive possibilities of coexistence, that of the decisive role played by Transylvanian historical traditions and the myth of the moral surplus inherent in the human character of minority individuals, which derives from the need to play roles such as “coping,” “service,” and “readiness to sacrifice” which paralyse the need for formulating real interests.

Gyimesi was preoccupied with Transylvanism – the interwar minority ideology – because she recognised that such a moral-centred ideological phenomenon holds the possibility of continuous political compromise from the outset. It is very difficult to draw the line between the morality of standing one’s ground and resignation. She raised the question whether the ideology of intellectuals heroically embracing minority destiny is a self-justification for not doing anything to change their situation? While writing her work she considered that the political tradition of compromise also contributed to the fact that her generation found itself in a minority situation even worse than that of the interwar period. It was her admitted purpose to point at the utopian, mythical features of this ideology that hid the real political interests of the minority and, instead of a strategy aimed at the satisfactory solution of the situation, compensated Transylvanian Hungarians with illusions. The manuscript was finished in the early months of 1985 when it seemed that an emotion-free, adequately abstract set of concepts was suitable to carry out a critique of the leading ideology of the interwar period in publishable form. She tried to avoid all those pathetic symbols and metaphors that – in the Romanian Hungarian spiritual life of the 1980s – defined in a concealed form the sense of identity among the Hungarians in Transylvania, and, by highlighting the positive values of the Transylvanian spirit and of the minority destiny, she tried to cope with the “double oppression” under the dictatorship.

The view of Transylvanism expressed in Pearls and Sand is characterised by a rather harsh critical voice. However, this is not performed in a direct manner. Criticism is primarily targeted at the clarification of concepts, determined by the need to grab the values polished into myths in their real essence. The detached dissection of the ideology components led to reactions that included labelling the author as destructive and describing the effects of the manuscript as damaging, on grounds that this merciless uncovering of the contradictory value structure of Transylvanism could easily discourage the reader from further accepting this seemingly hopeless minority situation. Beside the rather self-critical view of the past which was at the same time directed at the present, Gyimesi was unable to offer arguments in support of hope, and could not offer a perspective regarding the future, as between 1985 and 1987 she saw no real chances of a change in the deprivation of rights which the Hungarians in Transylvania had to endure. She considered it important to perform an accurate assessment of the situation and of minority awareness, to express the need for reflection, the desire for spiritual detachment, the system of analytical concepts by which she could identify even the most delicate contradictions.

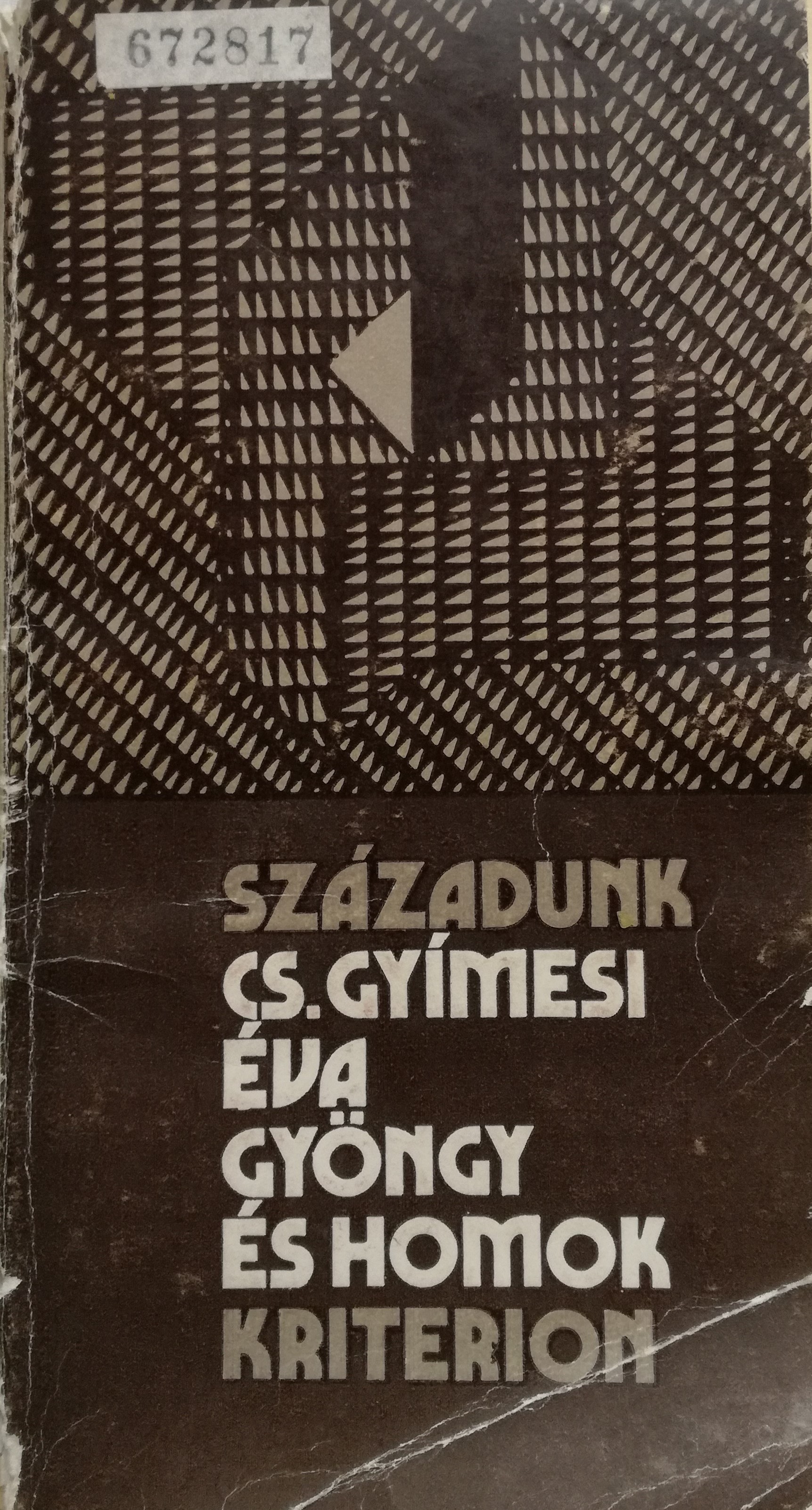

The study could not be published. It was confiscated by the Securitate for the first time on 1 October 1985, during a home search conducted at the author’s residence. Gyimesi had to provide translations of random excerpts from her study to her interrogators. Almost a year later, on 30 August 1986, the Limes circle organised by Gusztáv Molnár provided the occasion for discussing the manuscript during a meeting in Ilieni, Covasna county. Sándor Balázs, Béla Bíró, Ernő Fábián, and Levente Salat were the authors of comments (I236674/4). They intended to publish this debate material along with the study “later on, when times turn more favourable.” On 7 February 1987 the Securitate conducted a home search at Gusztáv Molnár’s flat in Bucharest and seized this work along with the Limes circle materials (I236674/1). However, by that time one copy was already in a “safe place.” The study was confiscated for the third time during the home search at Gyimesi’s residence on 20 June 1989 (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).

Gyimesi intended her study – finally published in 1992 after the regime change – to be a “warning mirror,” which would prevent Transylvanian Hungarians from falling into the traps of self-deception inherent in interwar ideology. The idealising moral view characteristic of Transylvanism, the patience exaggerated to the point of helplessness, the tendency to embrace suffering could get in the way of the struggle for human rights. Gyimesi held the opinion that a balance had to be found between the Transylvanist ideology of survival and the legal and political guidelines of the struggle. Furthermore, she believed that there was a need not only for emotional-moral reconciliation but, first of all, for a legal framework to ensure a humane, worthy life so that Hungarians in Transylvania could lead a harmonious, full-fledged life in Romania despite their minority status.